Appendix 1 – Rapid Review

Executive Summary

We are witnessing a growing trust divide in Australia which has increased in scope and intensity since 2007. There is widespread concern among scholars and in popular commentary that citizens have grown more distrustful of politicians, sceptical about democratic institutions, and disillusioned with democratic processes or even principles. Indeed, David Thodey, the Chair of the current Review of the Australian Public Service (APS) has highlighted his concern with the trust divide between government and citizen and argued that “Trust is a foundation stone for good [APS] work”.[1]

The purpose of this rapid review is fourfold, to investigate: 1) why trust/distrust matters; 2) whether and how declining trust is impacting on public experience of services; 3) how trust influences public behaviour such as the uptake of services; and 4), how the Australian Public Service (APS) can enhance the quality of public service production and use the service experience as a space for trust building. The review evaluates academic and grey literature that addresses these four areas of inquiry and develops a framework for subsequent qualitative research on public service production in regional Australia.

Key findings

Defining trust

We understand trust as a relational concept about ‘keeping promises and agreements’ (Hetherington, 2005). This is in keeping with the OECD’s definition where trust is “holding a positive perception about the actions of an individual or an organization” (OECD 2017: 16). For the purposes of this study, this would mean that trust in Australian public services requires government to deliver services that citizens’ value to a satisfactory level of performance.

Why trust/distrust matters

We discover that there are two main literatures that seek to make sense of these issues – the interdisciplinary literature on political trust and the public management literature on the changing nature of public service production.

With reference to the former literature, we note that weakening political trust: erodes civic engagement and conventional forms of public participation; reduces support for progressive public policies and promotes risk aversion and short-termism in government; and, creates the space for the rise of authoritarian-populist forces.

There are also implications for long-term democratic stability as liberal democratic regimes are thought most durable when built upon popular legitimacy. We also observe that it is extremely difficult to divorce public attitudes to politicians from public attitudes towards the quality of public service production.

However, as it is beyond the decision-making authority of the APS to address the problem of declining public trust with politicians, it makes better sense to focus attention on how the APS can deliver the best service experience possible and contribute to bridging the trust divide. This draws us inexorably towards supply-side theories of trust which focus on enhancing the quality of public service production. Trust in public services matters because this is where citizens interact with government and an opportunity is provided for strengthening the quality of democratic governance. Public service design and delivery is a fertile space for trust building.

What do Australians think about the services they receive?

Findings from the Citizen Experience Survey undertaken by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet indicate that despite similar satisfaction rates with public services as urban citizens, and similar levels of effort to access and receive public services, only 27 percent of regional Australians trust Australian government public services, compared with 32 percent of urban citizens. These low levels of trust, despite high levels of satisfaction, highlight that government performance (where here trust in public services is a proxy) is only one factor driving citizen’s confidence in government. This observation is in keeping with the secondary literature which views trust as a multi-dimensional problem requiring a broad range of responses.

Barriers and enablers to effective public service delivery

Box i presents an overview of the key barriers and enablers to public service production identified in the review.

Box i. Barriers and enablers to quality public service production

| Delivery barriers | Enablers |

|---|---|

| Lack of proactive engagement from government with users | Personalisation of public services |

| Users experience difficulty finding the right information, at the right time, in the right context | Establish a single source of truth across government information |

| Access to services is hindered by the complexity of government structures | Join-up, collaborate simplify and ensure “line of sight” |

| Users are uncertain about government entitlements and obligations | Proactive engagement from government through strategic communication |

| Public services are not meeting user service delivery expectations | Create service charters and incentivise performance |

| Users are being required to provide information multiple times | “Tell us once” – integrated service systems |

| Inconsistent and inaccessible content | Adopt user-first design principles |

| Complexity of tools provided by government | Simplify around user needs |

The majority of informants we interviewed as a component of this project, argued that a culture shift was required in the way Commonwealth departments and agencies manage and deliver public services to meet the Thodey aspiration of “seamless services and local solutions designed and delivered with states, territories and partners”. Although many noted that the process of change was underway. Five specific reform themes loomed large in discussion:

- Problem seek – see user feedback as an opportunity for progress. Take all complaints seriously and use simulators to make progress (e.g. ATO simulation lab, co-lab). Consider complaints at executive board level with reporting requirements.

- Use the APS footprint to facilitate whole of APS collaboration in community engagement.

- Collaborate whole of government in policy design and delivery through shared accountability mechanisms and budgetary incentives.

- Practice co-(user) design by default and use behavioural insights to improve our understanding of the needs and aspirations of target groups and develop personalised service offerings.

- Develop opportunities for dynamic engagement with users through inclusive service design and strategic communication.

There is significant evidence to demonstrate that the application of user-first design principles and the personalisation of public services can improve take-up of services and trust in government more broadly.

Indices for the qualitative analysis of public service production in regional Australia

We have therefore designed a set of indices to help us measure the relationship between trust and the quality of public service production. These include:

Trust as Competence (responsiveness and reliability)– the capacity and good judgement to effectively deliver the agreed goods/mandate;

Trust as Values (integrity, transparency and fairness)– the underpinning intentions and principles that guide actions and behaviours;

Trust as Satisficing – the degree to which citizens’ expectations of a service have been satisfied.

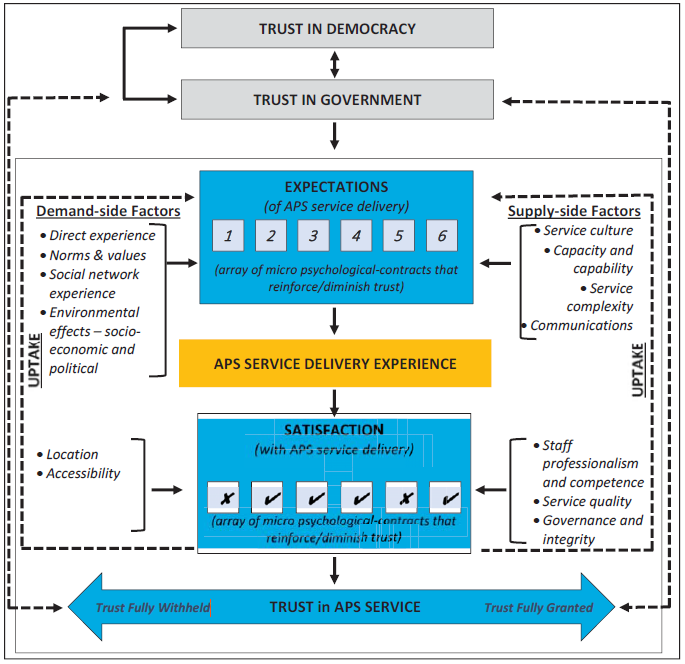

The review concludes by acknowledging that trust is a complex and multi-dimensional concept with many of these dimensions overlapping in practice. It therefore synthesises and clarifies the various drivers and dimensions of trust into a single trust framework (see Figure 5). In this framework we recognise the importance of trust in government, providing a feedback loop between trust in public service production and trust in government. We describe a citizen’s expectations of a public service not as a block box, but as an array of micro-contracts, each with their own conditions of satisfaction and levels of importance.

Introduction

Context

The Australian economy has experienced twenty-seven years of economic growth. A remarkable performance that is unprecedented both historically and in comparison with other OECD countries over the period. Yet, during the same time Australia has suffered a period of democratic decline and the depth of that decline has increased dramatically since 2007 (Stoker et al., 2018a). The level of democratic satisfaction has decreased steadily across each government from 86 percent in 2007 (Howard), to 72 percent in 2010 (Rudd), 72 percent in 2013 (Abbott) and 41 percent in July 2018 under Malcolm Turnbull. Australia’s least trusted institutions are: political parties (16%), web based media (20%), print media (29%), trade unions (30%), federal government (31%) and television media (32%). Australia’s least trusted professions are: MPs (21%), government ministers (23%), trade unionists (26%) and journalists (28%). And more than 60 percent of Australians believe the honesty and integrity of politicians is low. In contrast, public servants are one of our most trusted professions (39%) after judges (56%) and GPs (81%).

The decline in democratic satisfaction is not peculiar to Australia but what is remarkable is that it is occurring in a period of affluence. It is unsurprising, for example, that certain European countries impacted by the worst excesses of the Global Financial Crisis and austerity politics should turn away from the established political order and look for a new form of populist politics. But apart from the evident rise in citizen expectations of government, why is this happening in Australia? Is it being experienced differently in urban, regional and rural Australia? And, what impact is it having on public experience of Australian public services?

Purpose

This rapid review investigates academic and grey literature that address four areas of inquiry: 1) explanation of what drives or undermines trust; 2) evidence of whether and how declining trust is impacting on public experience of services; 3) evidence of how trust influences public behaviour such as the uptake of services; and 4), how the Australian Public Service (APS) can enhance the quality of public service production and use the service experience as a space for trust building.

The cumulative compilation of this evidence base will help the ‘Understanding public trust in Australian public services across regional Australia’ project better understand the drivers, barriers and enablers of public trust in the delivery of Australian public services in regional areas. In combining practical service delivery guidelines from the literature and a comprehensive understanding of how trust is built, this project will provide a valuable contribution to understanding regional service delivery through a nuanced lens of theory and practice.

Structure

The review is organised into five sections which combine to provide a cumulative understanding of trust in government and public services.

Section 1 provides an operational definition of trust to inform subsequent empirical work, explores the nature and relevance of the trust problem in the context of the operations of contemporary democracies and presents a case for why trust in government and by implication public services is important.

Section 2 outlines various demand and supply side theories that can help explain what is driving trust or its absence and demonstrates that trust is a multi-dimensional, “wicked” problem that requires a broad range of responses.

Section 3 reviews the evidence on public perceptions of the quality of the supply of public services in Australia.

Section 4 assesses the quality of the management of public services in Australia.

And Section 5, presents a conceptual frame, key indicators and research questions to guide qualitative research on the quality of public service production in regional Australia.

Defining and valuing trust

Before we can seek to understand the drivers of trust for public services in regional Australia, we first need to understand what we mean by trust. Trust is a complex, multi-dimensional concept with no agreed definition within the literature. However, there is sufficient common ground to understand trust as a relational concept about ‘keeping promises and agreements’ (Hetherington, 2005). The OECD’s comprehensive review of trust and public policy provides a slightly more detailed definition of this understanding of trust where trust is “holding a positive perception about the actions of an individual or an organization” (OECD 2017: 16). For the purposes of this study, this would mean that trust in Australian public services requires government to deliver services that citizens’ value to a satisfactory level of performance.

While this OECD definition provides a useful starting point, it is important to acknowledge that there are various additional dimensions of trust that are relevant to this study. For example, trust can be categorized based on ‘what’ is being trusted such as interpersonal trust which is about trust in other people and typically based on their adherence to shared values and/or norms, or institutional trust (systemic trust) which is about having trust in institutions or organisations to behave in a fair and honest manner (OECD 2009 & 2017). Similarly, trust can be categorized by how it is formed, cognitive trust for example is based on rational or experience-based perceptions (see: OECD 2017; and McKnight, Cummings, and Chervany 1998), while affective trust is informed by an individual’s emotions (OECD, 2017).

Given that the delivery of public services is an individual experience and often involves personal interactions with front-line service providers (i.e. via telephone, email, or face to face), all these forms of trust are potentially valuable when attempting to understand public trust in public services. Interpersonal and emotional trust is invoked in dealing with service providers while cognitive trust is determined based on the experience of the service delivery process and outcomes, all of which may combine to cast judgement on the level of institutional trust to be granted. These indicators of trust in public services will be discussed further in Section 5.

It is also important to recognise that trust is not an objective measure of government performance (Welch et al., 2004). Rather, trust is a subjective cognitive reflection of citizen perceptions based on available information and experience (Kim et al., 2017). As Sims (2001), observes citizen perceptions of government performance can be highly flawed as they are often shaped by media framing of contemporary issues and the public’s impressions based on poor information and personal prejudices. As such, trust is a complex and potentially “wicked” problem with multiple dimensions and causes (Stoker et al., 2018b).

Why is trust in Government and Public Services important?

There are at least three main reasons why a lack of trust may be problematic. First, it can undermine political engagement. Martin’s (2010) pioneering work in Australia shows that lack of trust impacts on levels of confidence in democracy, willingness to vote and take up of protest style activities and concludes that ‘the consequences of low levels of political trust may not be as dire as some feared… (but that) … there are grounds for concern’. Lack of trust in mainstream politics is a key factor in pushing citizens towards more populist alternatives. Second, lack of trust may make the general business of government harder to deliver. Marien and Hooghe (2011) using data from European countries, find that low political trust is strongly correlated with citizens’ willingness to tolerate illegal behaviour and potentially commit criminal acts themselves. Hetherington (2005) has expanded on these concerns to explore the impact of lack of trust on limiting what policy issues government can effectively tackle concluding that ‘scholars have demonstrated that declining trust has had important effects, mostly undermining liberal domestic policy ambitions.... Put simply, people need to trust the government to support more government’. Third, lack of political trust may make long-term policy problems less likely to be addressed. Politicians may also feel they lack the legitimacy necessary to request sacrifices from citizens (of the kind often required to solve major policy problems).

Trust requires integrity in practice and accountability for delivery; where trust is lacking the general business of government is much harder to deliver. Put simply, people need to trust the government to support more government (see Marien and Hooghe, 2011; OECD 2017).

In general then, trust is viewed to be integral for effective government. Trust stabilizes the relationship between government and citizens, providing the glue that facilitates cooperation on the provision of collective goods (Stoker et al. 2018; Van Ryzin 2011), compliance with rules (Van Ryzin 2011), democratic inclusion and ultimately social cohesion (OECD 2017; Miranti and Evans 2017; Stoker et al. 2018a).

Public services as a space for trust building

Evidence in the literature also indicates that high quality public services can lead to satisfied citizens and consequently improved trust in government (see: Van de Walle and Bouckaert, 2003; Yang and Holzer, 2006 in OECD 2017 p.48). This ‘micro-performance hypothesis’ linking public service delivery to trust in government is supported by Australian-based research which shows that public trust is partly shaped by citizen perceptions of the performance of government; particularly the quality of the provision of public services (Stoker et al., 2018b and Rothstein 2018). Here trust in government is viewed to be the glue that provides functional citizen–government relationships (Kearns 2004) and is essential for the achievement of stable governance systems and features such as:[2]

- Compliance with laws and regulations

- Cooperation in the provision of collective goods

- Reduced transaction costs as it is not necessary to constantly monitor behaviour

- Effective political engagement

- Legitimacy to act on long-term policy problems

- Confidence in the government to deliver basic functions

- Market confidence

- Social cohesion

- Effective crisis response and cooperation during emergency situations

- Leadership on key geopolitical issues

Better understanding trust in public services is therefore important because as the OECD (2017: 4) puts it – “trust is not only an indicator of success: it is, more significantly, one of the ingredients that makes success – for a business or for a government – possible.” Trust in public services matters because this is where citizens interact with government and an opportunity is provided for strengthening the quality of democratic governance (Van Ryzin 2011).

Supply and demand-side theories of trust

There is no one simple explanation for what drives or undermines trust. The research on the issue is one of the most voluminous in the social sciences and has been a concern in many countries for decades. The literature can be loosely organised around demand-side and supply-side theories of trust (Stoker and Evans, 2018).

Demand-side theories focus on how much individuals trust government and democratic politics and explore the key characteristics of the citizenry. What is it about citizens, such as their educational background, class, location, country or cohort of birth that makes them trusting or not? What are the barriers to citizen engagement? And what makes citizens feel that that their participation could deliver value? In general, the strongest predictors of distrust continue to be attitudinal and are connected to negativity about politics.[3]

Demand-side interventions therefore focus on overcoming various barriers to social, economic or political participation (or well-being). Most interventions tend to focus on dealing with issues of social disadvantage through education, labour market activation, public participation, improved representation, place-based service delivery and other forms of empowerment such as the provision of citizenship education to enhance political literacy (see Table 1).[4]

Supply-side theories of trust start from the premise that public trust must in some way correspond with the trustworthiness of government. The argument here is that it is the performance (supply) of government that matters most in orienting the outlooks of citizens, together with its commitment to procedural fairness and quality.

Supply-side interventions therefore seek to enhance the integrity of government and politicians, and the quality and procedural fairness of service delivery or parliamentary processes through open government or good governance. This normally includes transparency, accountability, public service competence and anti-corruption measures (see Table 1).

A further challenge in bridging the divide between citizens and government is that reforms that seem to provide part of the solution can sometimes make the problem worse. Offering more participation or consultation can turn into a tokenistic exercise, which generates more cynicism and negativity among citizens. The conclusion from much of the academic and practice-based literature is not that more participation is needed but that better participation is needed (Evans, 2014).[5]

Given that the Citizen Experience project focuses on how we can use the public service experience as a space for trust building between government and citizen our attention is best placed on the supply-side literature.

Table 1. A selection of demand and supply-side interventions to address the trust divide

Demand side problems and solutions

| Problem | Intervention | Design Principles |

|---|---|---|

| Need for education to increase understanding and capacity of citizens | Better Citizenship education | Input through programs of “learning and doing” will build citizens who are confident and pragmatic enough to build trust |

| Citizens/stakeholders want more of a say as they become more challenging and critical | Quality participation | Contingent on the purpose of the engagement. Varied with different foci on hard to reach groups, deliberation and selection by sortition. Having a say in a decision increases the prospects of trust |

| Opportunities to exploit capacity created by new technologies | Internet politics | Build on surge and waves of interest to deliver rapid responses to public concerns and build trust |

Supply side problems and solutions

| Problem | Intervention | Design Principles |

|---|---|---|

| If government did the small things in service delivery well this would improve levels of trust to tackle bigger problems | Improve the quality of service delivery | User-centred design, use innovation and new technology to increase customer satisfaction and improve performance in measurable ways |

| Closed government, corrupt practices | Open government and indicative transparency measures | People trust processes that are clear, transparent and accountable. Focus on driving out the practice and even the appearance of corruption or malpractice |

| Representative democracy has lost legitimacy because of the financing of parties and elections and the representative failings and poor practices of elected assemblies | Improved citizen-party linkage | Regulation of election spending, reform of party system, change parliamentary practices |

| The way that political choices and decisions are presented through new and traditional media creates a climate of distrust | Communication dynamics | Encourage through soft regulation and influence support changes in communication to better manage tension between freedom of media and a better governance context |

Enhancing Public Service performance

If the focus is on the performance of government to build trust one suggestion is that the best way forward is to do service delivery better. Public management reform advocates argue that “there’s a powerful – and positive – case that government officials can improve government’s standing by treating their citizens in trust-earning ways”.[6] These strategies might involve demonstrating good performance, creating positive customer experiences and transparently demonstrating the effort and commitment that goes into public service. Others might see improved digital capacity and service as a way of building trust in government;[7] although some evidence suggests that it is possible to boost the standing of the agency involved but not necessarily government as a whole.[8]

However, it should be noted that providing performance data – the bread and butter of modern government – so that citizens can judge if promises have been kept does not always produce more trust. Rather, it can lead to government officials trying to manipulate the way citizens judge their performance. Positive data is given prominence, less helpful data sometimes hidden. On the ground, frontline public servants and many citizens find the claims of success contrasting with their own more negative experiences. Far from promoting trust, the packaging of performance may in fact have contributed to the emergence of populism and loss of trust by citizens.[9]

Nonetheless, there is significant support within the literature for the micro-performance hypothesis; that by improving public services we can improve trust in government due to improved satisfaction and associated attitudes towards government, with Guerrero (2011) going as far as saying that the performance of public services is a predictor of trust in government.[10] As explained by Hetherington (1998) and Morgeson and colleagues (2010), public services are a component of the government and hence trust towards public services should help reinforce trust in the government as a whole.

Public perceptions of the quality of the supply of public services in Australia

This section focuses on reviewing the findings of specific APS survey research which has sought to evaluate public perceptions of the quality of Australian public service production. Four sources of data are considered including key findings from: 1) PM&C’s Citizen Experience Survey; 2) Telstra’s 2017 Connected Government Survey; 3) the Digital Transformation Agency’s (DTA) GovX team’s recent work on “common pain points” experienced by the public in their interaction with government services; and 4) the recent 2019 review of business.gov.au in the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science (DIIS). The findings are integrated in response to two questions: what do Australians think about the services they receive? And, do Australians have preferences in terms of delivery systems?

What do Australians think about the services they receive?

Preliminary findings from the Citizen Experience Survey undertaken by PM&C indicates that when comparing experiences of people in regional and remote areas compared to those in urban areas (i.e. major cities), there are similar satisfaction rates with public services, and similar levels of effort to access and receive public services, but only 27 percent of regional Australians trust Australian government public services, compared with 32 percent of urban citizens. These low levels of trust, despite high levels of satisfaction, highlight that government performance (where here trust in public services is a proxy) is only one factor driving citizen’s confidence in government (Sims 2001). Rather, government performance – and with it citizens trust in public services, trust in government and trust in democracy – is the result of complex interacting processes which reach beyond service delivery, including: policy and program design which attempts to reconcile diverging interests and balance numerous political and resource constraints; media framing of government performance; and, the behaviour of political elites (Sims 2001; Stoker et al. 2018b). Box 1 presents an overview of the key findings from the Citizen Experience Survey demonstrating that we cannot rely on the proposition that trust is an outcome of citizen expectations of a service and satisfaction with a service (see for example Morgeson 2012; OECD 2017).

Nonetheless, it is also evident that through the use of user-first principles of service design it is possible to identify common problems in the public’s experience of service. The DTA GovX team (2019), for example, has conducted a “common pain points” project with target groups of citizens which analyses “how people interact with government as they experience different events in their life, such as looking for work or caring for a loved one”. The findings provide a set of action points for improving the quality of the service experience (see Box 2). We will revisit these in the next section.

Box 1. Key findings from the Citizen Experience Survey

- Satisfaction (54%) with service outcomes is higher than trust (29%).

- 60 per cent of respondents are “non-aligned”; neither “trusting” or “distrusting”.

- Service experience during significant life events affect trust in the APS.

- Personal individual service delivery experiences drive overall trust.

- Australians trust the APS to use their data responsibly, but don’t trust them to store it securely.

- Trust is lower in regional (28%) in contrast to urban (34%) areas.

Do Australians have preferences in terms of delivery systems?

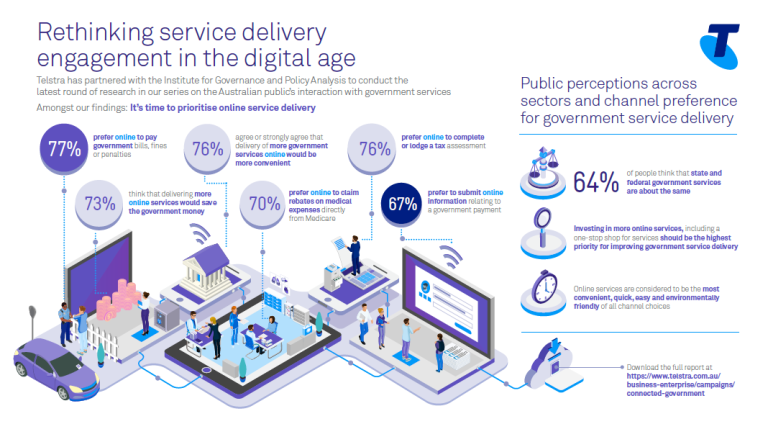

We recently conducted a national survey for Telstra on Australian attitudes towards digital public service production[11] and we found that: there is a sustained willingness amongst the Australian citizenry to use online services and a preference for on-line services over other delivery channels; the public sector is still perceived to be behind the private sector on key measures of service delivery but Australian citizens want digital services and don’t really care whether they are delivered by public or private sector organisations; confidence in government to deliver effective public policy outcomes is very low but there is a belief that digitisation could be used as an effective tool for rebuilding trust with the citizenry; and, the vast majority of the Australian public endorsed and expected the APS to engage in experimentation and service innovation (see Figure 1). Table 2 presents a snapshot of satisfaction drivers by channel in the Department of Human Services. In contrast, it shows that “face to face” channels remain the most effective driver of citizen satisfaction; although it is equally evident that the mix of channels is important to respond to the different needs of citizens.

Box 2. Common pain points in government-citizen interaction

- Lack of proactive engagement from government with the user

- Difficulty finding the right information, at the right time, in the right context

- Services hindered by the complexity of government structure

- Uncertainty about government entitlements and obligations

- Not meeting service delivery expectations

- Users being required to provide information multiple times

- Inconsistent & inaccessible content

- Complexity of tools provided by government

Source: DTA GovX 2019

Figure 1. Public perceptions across sectors and channel preference for public service delivery

In the first quarter of 2019 a review was conducted of Business.gov.au in DIIS.[12] The purpose of the review was to assess whether the needs and aspirations of small and family business owners are being supported effectively by business.gov.au and to provide recommendations on how the service experience could be enhanced. The recommendations draw on quantitative surveys of small business users conducted by the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science in 2013, 2015 and 2017 (Winning Moves, 2017). The research provides us with some key lessons for the public service system as a whole in relation to digital service delivery:

- User centred design is critical to delivering a high quality service experience.

- Small business owners want a trusted, one-stop shop to access the government information and assistance that they need. It should not mirror government internal structures (federal, state, local) and content should not be dispersed across multiple agencies, platforms and technologies (various applications and websites). Hence digital services should have a clear vision and scope.

- Small business owners expect on-line services to be accessible from a range of devices and easily navigable (functionality).

- Small business owners desire relevant and practical content that is tailored for their personal and user journey (personalisation).

- Appropriate channels of communication should be used to heighten awareness of the service. Although satisfaction with business.gov.au is high (93%), awareness is low (44%). Intermediaries (in this case accountants, bookkeepers, business advisers, and industry and professional associations are key points of contact for small business) can be better leveraged to push out relevant information that meets user needs.

Table 2. A snapshot of satisfaction drivers by channel in the Department of Human Services

| Centrelink | Child support | Medicare | ||||

| Driver | Face to face | Phone | Online | Mobile Apps | Phone | Face to Face |

| Perceived quality | 79.9 | 74.9 | 70.7 | 78.8 | ||

| Personalised service | 83.7 | 80.3 | N/A | N/A | 81.2 | 91.5 |

| Communication | 83.1 | 80.5 | 77.3 | 82.2 | 82.9 | 92.6 |

| Time to receive service | 71.5 | 51.7 | 71.6 | 78.5 | 58.7 | 71.1 |

| Fair treatment | 91.5 | 90.9 | N/A | N/A | 85.6 | 94.4 |

| Effort | 77.9 | 67.5 | 68.4 | 77.1 | 70.4 | 83.2 |

| KPI result | 81.2 | 74.1 | 72.0 | 79.0 | 79.0 | 86.1 |

Source: Senate Estimates July 2018 to February 2019

*mobile Apps as a channel added from October 2018

n.b. work is underway to include the online channels for Child Support and Medicare

Summary

The data presented in this section is in keeping with the core findings from the secondary literature on the take-up of digital public services. For example, Carter and Belanger (2005) found that trustworthiness of e-government services influenced service uptake; and, Lee and Turban (2001) observed that citizens need to trust both the agency and the technology.

The broader literature on public service delivery in regional areas does provide some guidance for further consideration of the potential to improve trust and the delivery of public services in regional Australia. Roufeil and Battye’s (2008) review of regional, rural and remote family and relationships service delivery highlights some significant challenges, but also points to the potential enabling factor of good trust between service providers and the communities – better service delivery is possible. They also highlight the importance of bespoke place-based delivery, that services cannot be delivered in rural areas like they are in urban areas as an important consideration (see also RAI 2015 who also emphasises flexibility in policy delivery and effective multi-level government governance arrangements).

This observation also suggests that it has become imperative for the Commonwealth Government to join-up social and economic development programs and services around regional development hubs to target and alleviate increased marginalisation.

Managing public services in Australia

This section focuses on the question how can the APS improve the management of public services? It draws on three main sources: the public management literature on better practice in delivering integrated public services in Westminster style democracies; findings from the DTA GovX team’s “common pain points” project; and preliminary findings from a set of interviews conducted for this project with APS thought leaders on how to improve the quality of public service production in Australia.

This will help us to identify the barriers to integrated service delivery in Westminster style democracies. It reviews a broad range of grey (practice-based) and academic based literature crystallised around two key issues that emerged from our findings in the previous section. Firstly, to identify the qualities of an ideal-type service delivery framework which will provide us with a benchmark for assessing the current state of play. Secondly, we will see that the establishment of integrated service delivery is seen as synonymous with achieving “line of sight” i.e. “Line of sight” is achieved when there is a clear line between the delivery of public services in the community and the high-level goals the organisation has set itself. Hence in this sub section we will focus on what stands in the way of achieving “line of sight” and being strategic in public service delivery.

What does an Ideal-type service delivery framework look like?

A service delivery framework (SDF) normally sets out the principles, standards, policies and operational constraints to be used to guide the design, development, deployment, operation and termination of services delivered by a service provider with a view to offering a consistent quality of service experience to a specific user community. For example, the 2008 Australian Government Service Delivery Framework (AGSDF) provides a whole of government roadmap to assist agencies to recognise and exploit the opportunities available for innovative and collaborative service delivery. Its purpose is therefore to achieve “line of sight” between goals, policies, programs, services and their achievement and generate public value.[13]

The most common strategic elements that are used to build an effective SDF include:

- Service culture – normally directed by the host Department’s strategic vision and delivered through its leadership principles, APS values, business processes and performance framework. Once a service delivery system and realistic service level agreements have been established, there is no other component more integral to the long-term success of a service organization as its culture.

- Organisational capacity and capability – even the best designed processes and systems will only be effective if carried out by organisations with the capacity, and people with the capability, to deliver. Organisational capacity and capability are key determinants of service excellence. In cases where services are augmented through forms of collaborative governance with States, territories or the community sector a focus needs to be placed on evaluating the quality of collaboration.

- Service quality – includes strategies, processes and performance management systems. The strategy and process design is fundamental to the design of the overall service management model.

- Service experience – involves elements of user intelligence, account management and continuous improvement. Successful service delivery works on the basis that the user/stakeholder is part of the creation and delivery of the service and then designs processes built on that philosophy – this is called co-creation or co-design.

- Service innovation and forward thinking – ensures that the organization has access to a strong evidence base on what works and has developed innovation systems to allow it to build effective knowledge networks to co-create new service products to stay ahead of the game.

By implication our qualitative inquiry should be cognisant of whether these five elements are effectively integrated within current service systems and achieving line of sight between goals, policies, programs, services and their achievement.[14]

Achieving “Line of Sight” and being strategic

The term strategy is very much part of the vocabulary of Westminster civil and public services but it is used quite indiscriminately. It is attached to a wide variety of statements without much apparent thought and often used only to confer importance and seriousness. Moreover, there is little analysis of the impact of strategic working on policy outcomes.[15]

Strategic organisations develop an understanding of their likely future operating environments. This brings obvious advantages for companies in the private sector, helping them to develop new markets, goods and services in advance of competitors and to increase profitability. For government, whether at national, departmental, state, regional, agency, local or sectoral level, a stronger understanding of potential futures gives it the capability to track which future is emerging, enabling organisations and policies to be more robust and resilient. Many parts of government do use strategic analysis to improve their planning and performance. But it is not a sufficient ambition for government simply to understand how to survive in a particular future. The job of government is to change the future, that is, to set-out a vision of a desired future and, through policies and achievement of those policies, to bring that future about. This is also a key component of its stewardship role which differentiates the permanent bureaucracy from the political class. Indeed this is the key difference between strategy work in the private sector – which is about optimal performance and profitability for their own organisations in whichever future comes about, and in the public sector – which is about achieving better outcomes for citizens. To make strategic thinking and delivery a reality, the political (elected) leadership of organisations and the permanent (unelected) leadership have to share an understanding of how to work strategically, not simply with each other but with their organisations and the world beyond.

Outcomes-based policy is more likely to motivate those who will achieve the results government seeks; front-line workers and citizens themselves. We find from our review of the literature that the theory of public value is posited as a helpful way of testing whether outcomes will enjoy the confidence of ministers and other accountable leaders.[16] Public value comprises three main components: services, trust and outcomes. One of the difficulties working in a government department or in many other parts of the public sector is that employees tend to be measured and rewarded for success in refining processes (for instance, better consultation, less regulation, the monetisation of benefits), or for helping to produce outputs (more nurses, more qualifications achieved) or for managing inputs (a bigger budget for recycling, a ten per cent saving in administrative costs) but are very rarely recognised for the contribution they make to achieving outcomes.

What is it that government organisations exist to achieve? The Roads to Recovery Programme supports ‘the maintenance of the nation’s local road infrastructure asset, which facilitates greater access for Australians and improved safety, economic and social outcomes”; the Army exists to win wars and keep the peace; Medicare exists to treat illness and promote health; schools exist to educate young people and help them to realise their full potential. When we express each of these aims in outcome terms, we release greater potential for the achievement of public value.

For instance: ‘People are able to travel by road safely and without delay’; ‘People live in a safe and secure world, with strong international institutions that keep the peace and uphold human dignity’; ‘People know how to stay healthy and receive effective treatment when they fall ill’; ‘Young people are motivated to learn and are supported in their learning by able teachers who help them to develop the skills and knowledge they need to fulfil their potential’.

Schools cannot alone improve education. Children and parents and peer groups are crucial to learning, so the outcome must be co-produced, not simply ‘delivered’ by schools. Similarly, highways alone cannot ensure that people travel speedily and safely; the amount of drivers and their behaviour, the nature of the vehicles that we use; the necessity to travel or the ability and inclination to work from home all contribute to the outcome.

Once an organisation has a strategic vision and a set of policies working to achieve that vision, it then needs to look at itself. The implementation of a strategic vision almost always requires change: change in the activities and behaviours of staff and of the organisation as a whole, including of budget allocations. If a strategy is constructed properly then it will be possible to construct objectives, indicators and feedback mechanisms that will enable government to measure and report on whether the outcomes are being achieved, not only by the organisation itself but by the wider delivery system. This is important so that the organisation can use public money efficiently and effectively. Accountability to the public, when handled honestly and accurately, can in turn build public value by increasing trust.

Any organisation should be able to express its reason for existence in a single sentence. For the supermarket Coles this is: “To offer real value to our customers by lowering the price of the weekly shopping basket, improving quality through fresher produce and delivering an easier, better shopping experience every day of the week”; for DIIS it is: “To enable growth and productivity for globally competitive industries”. In each case the statement of core purpose should be the product of a strategic process that has meaning for the organisation’s customers, staff and stakeholders. (Note: statements like ‘We will be the best at x’ or ‘We will be the leading provider of Y’ are ineffective statements of core purpose, because they offer no definition of what the organisation stands for).

In summary, to create strategy in government we need an understanding of plausible potential futures, a desired vision of the future, a set of outcomes that create public value, organisational alignment and allocation of resources throughout the delivery system to support achievement of those outcomes, together with accountability and feedback mechanisms to measure attainment, plus clear core purpose. These together can give us ‘line of sight’: a way for leaders – both political and permanent – to see the links between strategic aims and intent, policy processes and delivery and achievement at the front line – and a way for the front line and citizens to see exactly the same things.

Typical barriers to achieving “Line of Sight” and being strategic

So what makes it so hard to be strategic in delivering services? The literature suggests that there are at least six main areas where difficulties arise in the implementation of public services.

- Delivery burdens. Daily operational pressures (the 24/7 media cycle, the three year electoral cycle) on both the political and permanent leadership can tend to ‘squeeze’ strategic working out of the system.

- Analysis. Strategic analysis can either be too short term and trend-based to help steer the organisation or too far-fetched and improbable to hold the attention of policy-makers.

- Poor “Line of sight”. Strategy work can seem to be exclusively about high-level goals, or it can seem to be purely about a particular set of policies, or it can appear to be a preoccupation with functional strategies or with delivery planning. Line of sight is achieved when there is a clear line between delivery in the community and the high-level goals the organisation has set itself. This requires the strong integration of policy, programmes and delivery.

- Product but not enough process. Strategies that create change within organisations and in the world beyond are the result of a process driven by those who work in the organisation and its stakeholders. Yet too often they are simply documents produced by a small group or by consultants which do not create new understanding, still less change. These strategies act like tightropes, from which the organisation must eventually fall, rather than as a compass enabling it to set and re-set its direction. This suggests the need for inclusively generated change management process with clear performance accountabilities enshrined in performance agreements and appraisal.

- Insufficient innovation and challenge. A common complaint in government and the wider public sector is that public servants are poor innovators. Strategy requires new understanding and a preparedness to do things in new ways, challenging received wisdom. Yet government tends to incentivise compliance and conformity in its employees and restrict challenge. Commitment to continuous improvement should be embedded in performance agreements and appraisal.

- Uncertainty about public value. Outcomes can be identified using sound analysis, but they also need both the mandate of political leaders and their sustained interest. This means that the organisation as a whole must be capable of focusing on a set of goals and returning to them again and again.

Evidence from the front-line on how to improve the management of services

As noted in the previous section, the DTA GovX team’s “common pain points” project analyses “how people interact with government as they experience different events in their life, such as looking for work or caring for a loved one”. The findings correlate with much of the evidence presented in the last two sections of this report and provide a set of action points for improving the management of the service experience (see Box 3).

APS thought leaders on how to improve the quality of public service production in Australia

We have interviewed 10 APS thought leaders for this project on how the APS can improve elements of service-delivery to drive higher levels of public trust. The majority of informants argued that a culture shift was required in the way Commonwealth departments and agencies manage and deliver public services to meet the Thodey aspiration of “seamless services and local solutions designed and delivered with states, territories and partners”. Although many noted that the process of change was underway. Five specific themes loomed large in discussion:

- Problem seek – see user feedback as an opportunity for progress. Take all complaints seriously and use simulators to make progress (e.g. ATO simulation lab, co-lab). Consider complaints at executive board level with reporting requirements.

- Use the APS footprint to facilitate whole of APS collaboration in community engagement.

- Collaborate whole of government in policy design and delivery through shared accountability mechanisms and budgetary incentives.

- Practice co-(user) design by default and use behavioural insights to improve our understanding of the needs and aspirations of target groups and develop personalised service offerings.

- Develop opportunities for dynamic engagement with users through inclusive service design and strategic communication.

Box 3. Barriers and enablers to quality service provision

| Delivery barriers | Service reform |

|---|---|

| Lack of proactive engagement from government with users | Personalisation of public services |

| Users experience difficulty finding the right information, at the right time, in the right context | Establish a single source of truth across government information |

| Access to services is hindered by the complexity of government structures | Join-up, collaborate, simplify and ensure “line of sight” |

| Users are uncertain about government entitlements and obligations | Proactive engagement from government through strategic communication |

| Public services are not meeting user service delivery expectations | Create service charters and incentivise performance |

| Users are being required to provide information multiple times | Establish “tell us once” – integrated service systems |

| Inconsistent and inaccessible content | Adopt user-first design principles |

| Complexity of tools provided by government | Simplify around user needs |

Hence, the evidence from the interviews also points to the need to build collaboration across the APS, enhance service-delivery reform, and ultimately, drive tailored responses that reflect the plurality of identities in Australia.

Indices for the qualitative analysis of public service production

This final section of the review seeks to operationalise the concept of trust in empirical research on public service production. To better understand how trust is lost, consolidated or gained, we need to understand how to measure it. There is an extensive literature that attempts to identify the key indices of trust. The literature tends to focus on three sets of indicators (OECD 2017: 21):

Trust as Competence – the capacity and good judgment to effectively deliver the agreed goods/mandate;

Trust as Values – the underpinning intentions and principles that guide actions and behaviours;

Trust as Satisficing –the degree to which citizens’ expectations of a service have been satisfied.

These sets of indicators are considered in more detail below.

Trust as competence (responsiveness and reliability)

Competence is not just a component of trust, but a necessary condition (see Forsyth, Adams and Hoy, 2011 in OECD 2017 p.21). Individuals and institutions need to be able to deliver on their agreed intentions in order to be trusted. Competence to deliver is further nuanced by two critical dimensions of trustworthiness[17] – responsiveness and reliability (OECD 2017).

For the delivery of government public services responsiveness brings democratic principles right back into the forefront. Public service responsiveness as a driver of trust recognises the core objective of government and associated public administration – to serve citizens (see: OECD 2017 and the 1999 Public Service Act). Responsiveness is about more than how governments organize themselves to deliver quality public services in a timely manner, it is also about providing authentic opportunities for citizen engagement in the design and delivery of their public services – respecting, engaging and responding to citizens (OECD 2017, see also Stoker et al., 2018a, 2018b).

Reliability refers to the capacity for individuals or institutions to be able to adapt and act appropriately in response to changing circumstances. A reliable government can minimize uncertainty by anticipating citizens’ needs and responding effectively with appropriate policy and programs, including public services. To be effective in responding, public services must first be reliable.

Trust as values (integrity, transparency and fairness)

Perceptions of trust are heavily influenced by values and the guiding motivations they set on future actions and behaviours (OECD 2017). The OECD (2017: 22) presents three values or dimensions of trustworthiness: i) integrity, ii) transparency and iii) fairness.

Research undertaken by Murtin and colleagues (2018) on trust and its determinants demonstrates that citizens’ perceptions of government integrity and institutional performance are the strongest determinants of trust in government. Integrity refers to “the application of values, principles and norms in the daily operations of public sector organisations” (Stoker et al 2018b: 19). It is the behaviour of individuals and institutions, and their ethics which determine how they conduct themselves, and in the case of government, how it safeguards the public interest over private interests. Integrity reinforces the credibility and legitimacy of individuals or institutions (OECD, 2017).

In behaving with integrity you behave ethically and adhere to established social norms and governance expectations. Integrity is the cornerstone of good governance (Stoker et al. 2018b), and in Australia, as in many democratic nations, good governance expectations would typically include the dimensions of transparency (transparent decision-making and the inclusion of stakeholder or citizens in the design and delivery of proposed actions such as public services), and fairness (consistency and equity in the distribution of costs and benefits of proposed actions across society).

In considering the full scope of integrity its connection with issues of procedural justice can be observed as an important driver of citizens’ perceptions (see Tyler 2001 & 2006). Many scholars have observed that in evaluating government, citizens base their approval not only on the delivery of policy outcomes, but also on ethical judgements of both the actions of political leaders and institutions and the fairness of political processes (see for example: Tyler 2001; Hibbing and Theiss-Morse 2002; Van Ryzin 2011; & OECD 2017). Similarly, the consistency of service delivery across socio-economic, geographic and cultural boundaries informs perspectives of fairness driving perceptions of trust (Guerrero, 2011; OECD 2017).

The review of trust undertaken by the OECD (2017) found three elements of process and behaviour affecting fairness outcomes: i) voice, an authentic opportunity to present interests and be informed on how such interests were considered in decision-making; ii) polite and respectful treatment, the capacity to co-operate without the fear of being excluded or exploited (citizen feels safe and valued as a member of society); and iii) explanations, the effective communication of information about relevant regulatory and administrative processes and reasons for decisions. While each of these elements need to be considered in the design and delivery of public services and broader policy reforms, these elements can predominantly be addressed through openness (voice and explanations), integrity (polite and respectful treatment).

Given this focus on ethical behaviours, implementing government integrity approaches can also have negative impacts on trust which needs to be considered. For example, transparency is an important component of government integrity through the provision of openness in government decision-making. Transparency is strongly linked to improved citizens’ trust (see for example Stoker et al 2018a, 2018b), with Park and Blenkinsopp (2011) identifying transparency as a predictor of trust and satisfaction. However, the link between transparency and trust is not so simple, with increased transparency potentially reducing levels of trust as controversial policy decisions and outcomes are shared publicly and highlighted by the media and/or political advocates (Margetts 2011; OECD 2017).

The interactions between the two dimensions, competence and values, also needs to be recognised when understanding the drivers of trust in government public services and designing associated policy reforms. A key example of this interaction is the importance of citizens’ participation. Participation works to both improve competence through assisting responsive government outcomes in the delivery of services tailored for the citizens needs reducing the gap between expectations and performance (Yang and Holzer 2006; Wang and Wart 2007); and improving integrity by enabling openness in policy and/or service delivery planning through transparency and inclusivity. This (and other potential interactions) highlights the need to consider the drivers of trust as a system rather than discrete dimensions.

This deeper understanding of trust as consisting of two interacting components, competence and values, enables a more informed and nuanced definition of institutional trust, the form of trust that this study is predominantly focused on. Again, following the work of the OECD, for this study of public governance institutional trust is defined as “A citizen’s belief that [the institutions of government] fulfil their mandates with competence and integrity, acting in pursuit of the broader benefit of society” (2017: 23). Trusting the Australian government to deliver effective public services that benefit all Australian citizens.

Trust and user satisfaction

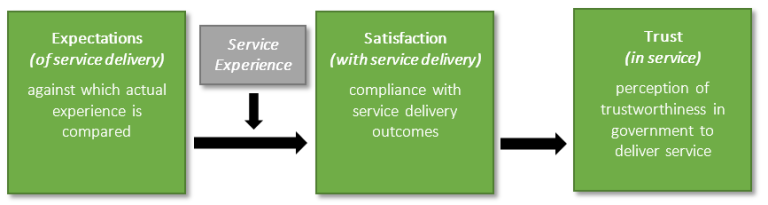

Trust is often seen as an outcome of citizens’ expectations of a service and satisfaction with a service (see for example Morgeson 2012; OECD 2017). While often statistically correlated, it is important to recognise that trust and satisfaction are distinct concepts (Fledderus 2015; Wang and Wart 2007). As discussed earlier, trust is the perceived competence and integrity of the government to design and deliver the service fairly to its citizens over time. Satisfaction, on the other hand, relates directly to the outcomes of service delivery in comparison to the citizens pre-conceived expectations (Bouckaert & van de Walle, 2003; Morgeson III 2012; Van Ryzin, 2015) depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 2. Process of trust development (Adapted from van Ryzin 2007 & Morgeson III 2012)

Many studies have found a strong correlation between satisfaction and trust (e.g. van Ryzin et al., 2004), with the relationship further highlighted by Vigoda-Gadot (2007) who found that satisfaction was the strongest predictor of trust in governance. However, it is important to recognise that there are many context-specific factors which also affect trust, including socio-economic characteristics, historical and political contexts, cultural factors, media etc. (OECD 2017). As such, satisfaction with public services is only one of many drivers of trust and while convenient, the depiction of trust development in Figure 2 is highly simplified and hides the multiple drivers influencing each element within the process as explored further in Section 3.

As observed in this review, there are numerous internal and external factors which can influence trust, captured both within and across the various trust drivers and categorised as demand-side or supply-side factors (see Table 1). Similarly, there are multiple drivers of satisfaction which again are predominantly captured within the various dimensions of trust (see Table 2). This overlap, as shown in Table 2, highlights that there are not in-fact a myriad of drivers affecting trust and satisfaction, but rather a set of core drivers which when implemented properly capture all the necessary pre-requisites for achieving trust – ideally by behaving with integrity and with that, implementing good governance. If a public service is designed and implemented following good governance practices it will:

- be a competent and well-managed process that is transparent and consistent in its approach (accountable, reliable);

- provide authentic opportunities for citizens voice in development and implementation (responsive);

- provide open and transparent information about the service and its governance, including privacy; will ensure adherence to ethical behaviours and intent to ensure equity of service provision for all citizens (values).

Table 2. Drivers and dimensions of trust and satisfaction in public services

| Trust Drivers | Satisfaction Drivers | ||||||

|

Professionalism (Capable and efficient officers, treated with dignity and respect) |

Information (clear and accurate information) |

Access & Coordination (Ease to access consistent and seamless service) |

Personalised Service (Service able to respond to individual needs) |

Privacy (Privacy is maintained and information available on privacy protocols) |

Effort (Level of effort required to engage and access services) |

||

| Competence |

Reliability (Predictable, dependable, adaptive, well-managed) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

Responsiveness (Accessible, timely, respectful, receptive and reactive to feedback) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Values |

Fairness (Equitable, open to citizens voice, polite and respectful treatment, effective explanation of process) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

Openness (Open to citizens voice and transparent on processes and outcomes) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

|

Integrity (ethical behaviours and good governance mechanisms) |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

Notably, most of these dimensions are supply-side factors – so what is the role of demand-side factors?

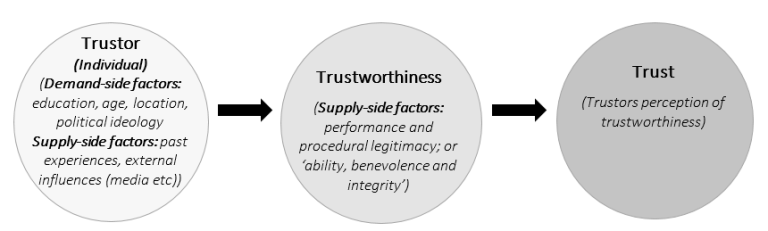

Demand-side factors

As noted previously, here we are only interested in indicators that the APS can influence in the context of public service production and can measure. Demand-side factors, are mostly related to the key characteristics of the individual citizen. Let’s pause here and think carefully about what we are trying to ‘measure’ or ‘influence’ – trust or trustworthiness? Cho and Lee (2011) spend some time explaining the difference between these discrete but related concepts, describing trustworthiness as being about characteristics of the trustee (supply-side factors) and trust being about the psychological state of the individual trustor (demand-side factors interacting with supply-side factors). That is, trust is an individual’s perception of the trustworthiness of another (i.e. individual, government, service etc.) (see Figure 3).

Three core dimensions of trustworthiness have been identified in the literature: ability, benevolence, and integrity.[18] Associated with competence, good intentions, and honesty and consistency, these dimensions of trustworthiness are eerily similar to those of trust e.g. responsiveness and values.[19] We therefore argue that it is more practical to focus on trustworthiness and the supply side factors that make the APS or a public service trustworthy.

Figure 3. The relationship between trust and trustworthiness

Source: adapted from Cho and Lee (2011)

In conclusion: conceptualising trust in the context of public service delivery

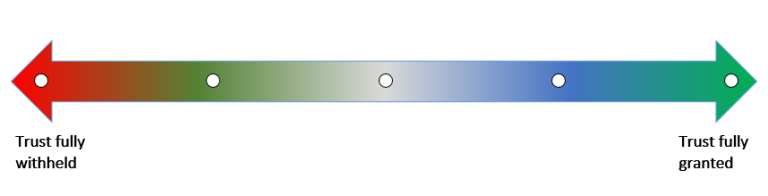

In determining the conceptual frame which will guide our qualitative research, we first need to understand the reality of trust in public service practice. Using the work of Rousseau (1989), we understand that as part of the process of public service delivery each of the interacting interpersonal and organizational relationships are operating within the limits of an individual’s ‘psychological contract’, an inferred subjective contract which sets out “the terms and conditions of a reciprocal exchange agreement” (Rousseau 1989 in OECD 2017, 16) between two parties (the citizen and the government for example). A lack of compliance with the ‘contract’ is perceived as a betrayal, resulting in a lack of trust. But trust is multi-dimensional. Using the multiple dimensions of trust, combined with the notion of psychological contracts, we can understand that trust is not binary, it is not simply a case that you have it or you don’t. Rather, trust is a series of micro psychological-contracts that cover the various trust drivers and dimensions, and they accumulate to determine what level of trust is granted or not, and under what conditions. Trust is grey, not black and white.

For example, an individual would have a series of subjective and inferred micro-contracts that require a public service to be easily accessible and capable to meet their needs in a timely fashion (trust - responsive), during the delivery of that service they expect their personal information to be treated with privacy (satisfaction – privacy), and be treated as a respected member of society (trust – fairness, satisfaction – professionalism). However, in their experience of the public service sought, despite the fair treatment and privacy of personal information, their needs might not be met in a timely manner. Does this mean they do not trust the public service outright? Or does it mean they trust the public servants to do their very best given the circumstances and will work with them to seek a satisfactory outcome and hence are willing to partially trust the public service on offer? Trust can therefore be considered along a spectrum from fully withheld to fully granted trust (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. A trust spectrum

Our measures of trust are typically based on direct questions, “Do you trust…?” not “What do you trust about ...?”. Rather than forcing a complex multi-dimensional concept into a binary or at best a Likert scale, we should be respecting our citizens capacity for rationale thought and ask them to dissect their trust judgements so as to better understand the logic(s) they use to evaluate trust (issues of cognitive or rational, and affective or emotional forms of trust).

With this understanding we can identify, prioritise and tailor communications and policy and program reform efforts. However, in practice this is not as simple as it sounds. Some researchers observe that citizens often have a single generalised perception of trust and find it hard to explain their logics when coming to a trust judgement (see Marien and Hooghe, 2011). Hence, in this qualitative study we provide the structure and opportunity for citizens to think past their initial preconceived judgements of trust and describe the rationale behind these judgments.

Acknowledging that trust is a complex and multi-dimensional concept with many of these dimensions overlapping in practice, this project will synthesise and clarify the various drivers and dimensions of trust into a single trust framework (see Figure 5). In this framework we recognise the importance of trust in government, providing a feedback loop between trust in public service production and trust in government. We describe an individual’s expectations of a public service not as a block box, but as an array of micro-contracts, each with their own conditions of satisfaction and levels of importance. These micro-contracts might be satisfied, or not, and it is this combination of compliance with the micro-contracts that determines the level of trust granted, if at all. The conceptual frame also deliberately includes the various demand and supply side factors which potentially influence trust outcomes at the expectation and satisfaction stages. It is important here to note the feedback loops from trust in the service and satisfaction with the service to expectations, where positive service delivery and trust outcomes are likely to increase expectations, and poor outcomes likely to decrease expectations.

Figure 5. Framework for understanding perceptions of trust in APS public service

References

Adams, B. et al., (2000), “Trust in teams: A review of the literature”, Report to the Defence and Civil Institute of Environmental Medicine. Human systems Incorporated, Guelph, Ontario, Canada.

Alonso, S., Keane, J. and Merkel, W. (eds), (2011, The Future of Representative Democracy, Cambridge: CUP.

Badri, M., M. Al Khaili and R.L. Al Mansoori (2015), “Quality of service, expectation, satisfaction and trust in public institutions: The Abu Dhabi Citizen Satisfaction Survey”, Asian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 420-47.

Boswell, Christina (2018), Manufacturing Political Trust. NY: CUP.

Bouckaert, G., & van de Walle, S. (2003), “Comparing measures of citizen trust and user satisfaction as indicators of “Good Governance”: Difficulties in linking trust and satisfaction indicators”. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 69 (3), 329–343.

Bovaird, T. (2007), “Beyond engagement and participation: User and community coproduction of public services”. Public Administration Review 67:846–60.

Carter, L. and Bélanger, F., 2005. The utilization of e‐government services: citizen trust, innovation and acceptance factors. Information systems journal, 15(1), pp.5-25.

Cho, Y. J., and J. W. Lee. 2011. “Perceived Trustworthiness of Supervisors, Employee Satisfaction and Cooperation.” Public Management Review 13 (7): 941–965. doi:10.1080/14719037.2011.589610.

Christensen, T. and P. Lægreid (2005), “Trust in government: The relative importance of service satisfaction, political factors, and demography”, Public Performance & Management Review, Vol. 28, No. 4, pp. 487–511.

Edwards, K., & Tanton, R. (2013). Validation of spatial microsimulation models. In R. Tanton & K. Edwards (Eds.), Spatial Microsimulation: A Reference Guide for Users (pp. 249–258). Springer.

Evans, M. and Stoker, G. (2016), ‘Political participation in Australia: Contingency in the behaviour and attitudes of citizens’, Australian Journal of Political Science, 51 (2), 272-287.

Evans, M., Stoker, G. and Halupka, M. (2016), "A Decade of Democratic Decline: How Australians Understand and Imagine Their Democracy", in Chris Aulich, (ed.) , From Abbott to Turnbull. A New Direction? Canberra: Echo Books, pp. 23–41.

Evans, M. and Halupka, M. (2017), Telstra Connected Government Survey: Delivering Digital Government:the Australian Public Scorecard, retrieved 18 May 2019 from: https://insight.telstra.com.au/deliveringdigitalgovernment.

Evans, M., Halupka, M. and Stoker, G. (2017), How Australians imagine their democracy: The “Power of Us”, Museum of Australian Democracy, Old Parliament House. Canberra: Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis (IGPA). Retrieved 18 May 2019 from: http://www.governanceinstitute.edu.au/research/publications/recent-repo…

Fledderus, J. (2015), "Does User Co-Production of Public Service Delivery Increase Satisfaction and Trust? Evidence From a Vignette Experiment", International Journal of Public Administration, 38: 9, 642–653, DOI: 10.1080/01900692.2014.952825

Glaser, M. A., & Hildreth, B. W. (1999), "Service delivery satisfaction and willingness to pay taxes: Citizen recognition of local government performance". Public Productivity and Management Review, 23(1), 48–67.

Guerrero, A. (2011), Rebuilding trust in government via service delivery: The case of Medellin, Colombia. World Bank, Washington, DC, http://siteresources. worldbank. org/EXTGOVANTICORR/Resources/303, pp.5863–1289428746337.

Gyorffy, D. (2013), Institutional Trust and Economic Policy, Central European University Press.

Hetherington, M.J. and Husser, J.A. (2012), "How trust matters: The changing political relevance of political trust". American Journal of Political Science, 56(2), 312–325.

Hetherington, M. J. (1998), "The political relevance of political trust". The American Political Science Review 92: 791–808.

Hetherington, M. (2005), Why Political Trust Matters. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hibbing, J.R., and Theiss-Morse, E. (2002), Stealth democracy: American’s beliefs about how government should work. Cambridge University Press.

Jacobs, A. and S.J. Matthews (2011), ‘Why do Citizens Discount the Future? Public Opinion and the Timing of Policy Consequences’, British Journal of Political Science, 42 (4), 903–935.

Janssen, M., Rana, N.P., Slade, E.L. and Dwivedi, Y.K. (2018), Trustworthiness of digital government services: deriving a comprehensive theory through interpretive structural modelling. Public Management Review, 20 (5), 647–671.

Kampen, J.K. et al. (2003), “Trust and satisfaction: A case study of the micro-performance”, Governing Networks, 319–26.

Keane, John. (2009), The Life and Death of Democracy, London, Simon & Schuster.

Kettl, D. (2017), Can Government Earn Our Trust? Cambridge: Polity Press.

Kim, S.K., Park, M.J. and Rho, J.J., (2017), "Does public service delivery through new channels promote citizen trust in government? The case of smart devices". Information Technology for Development, 1–21.

Lee, M.K. and Turban, E. (2001), "A trust model for consumer internet shopping". International Journal of electronic commerce, 6(1), 75–91.

Levi, M., & Stoker, L. (2000), "Political trust and trustworthiness". Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 475–507.

McKnight, D Harrison, Larry L. Cummings, and Norman L. Chervany (1998), "Initial trust formation in new organizational relationships". The Academy of Management Review 23: 473–90.

Margetts, H. (2011), “The Internet and Transparency.” The Political Quarterly 82 (4): 518–521. doi:10.1111/poqu.2011.82.issue-4.

Marien, S. and Hooghe, M. (2011), "Does political trust matter? An empirical investigation into the relation between political trust and support for law compliance". European Journal of Political Research, 50 (2), 267–291.

Martin, A. (2010), ‘Does Political Trust Matter?’, Australian Journal of Political Science, 45 (4), 705–712.

Miranti, R. and Evans, M. (2019), "Trust, sense of community, and civic engagement: Lessons from Australia". Journal of community psychology, 47(2), 254–271.

Murton, Fabrice, Lara Fleischer, Vincent Siegerink, Arnstein Aassve, Yann Algan, Romina Boarini, Santiago Gonzales, Zsuzsanna Lonti, Gianluca Grimalda, Rafael Hortala Vallve, Soonhee Kim, David Lee, Louis Putterman and Conal Smith (2018), ‘Trust and its determinants: Evidence from the Trustlab experiment’, OECD Statistics Working Papers, 2018/02, Paris : OECD Publishing..

Norris, Pippa (1999), A Virtuous Circle. NY: Cambridge University Press.

OECD (2009), Focus on Citizens: Public Engagement for Better Policy and Services, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264048874-en.

OECD (2017), Trust and Public Policy: How Better Governance Can Help Rebuild Public Trust, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, available on-line at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264268920-en (retrieved 23 January 2019).

Park, H., and J. Blenkinsopp (2011), “The Role of Transparency and Trust in the Relationship between Corruption and Citizen Satisfaction.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 77 (2): 254–274. doi:10.1177/0020852311399230.

Regional Australia Institute (RAI) (2015), Delivering Better Government for the Regions. Regional Australian Institute Discussion Paper. November 2015. Accessed April 29 2019, http://www.regionalaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Delivering-Bette…

Rothstein, B. (2018), ‘Fighting Systemic Corruption: The Indirect Strategy’, Daedalus, 147, 3: 35-49.

Roufeil, L. and Battye, K. (2008), Effective regional, rural and remote family and relationships service delivery. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Sims, H. (2001), Public confidence in government and government service delivery (p. 41). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre for Management Development.

Small Business Advisory Group Report (2019), Unlocking the Potential of Business.gov.au, Canberra, Department of Industry, Innovation and Science.

Stoker, G. (2017), Why Politics Matters: Making Democracy Work, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stoker, G., Evans, M., and Halupka, M. (2018a), Democracy 2025 Report No. 1. Trust and Democracy in Australia: democratic decline and renewal (2018), Canberra, MoAD. Accessed 16 May 2019 from: https://democracy2025.gov.au