Understanding and exploring trust in public service delivery

This section presents a summary of the Rapid Review which is provided in full in Appendix 1

There is no unified literature that focuses directly on the issue of trust in government services in regional Australia. There are significant literatures that focus on different aspects of trust/distrust in government and the management and delivery of public services in general. On the latter issue we can find a small number of specific studies that reflect on the difficulties of delivering specific types of services to regional, rural and remote communities. These studies tend to focus on various barriers and potential enablers to primary and specialist service delivery in areas such as family, health and disability services.

There is a literature on community capability, resilience and cohesion in regional Australia which addresses issues of institutional capacity that is relevant but not a core concern of our study. The contention here is that regional communities with a critical mass of public and social institutions and associated networks are more likely to engender public trust in government services; there is also a much larger literature that focuses on service delivery in remote indigenous communities which is outside the scope of this study.

On the issue of how public organisations can address delivery problems there are three pertinent literatures for this study: that on integrated service delivery and mastering complexity through coherence; citizen-centred design thinking; and, long-standing literature on implementation gaps or slippage.

These literatures form the focus of our attention in this rapid review.

What is trust and why is it important for Australian public service delivery?

Defining Trust

We understand trust as a relational concept about ‘keeping promises and agreements’ (Hetherington, 2005, p. 1). This is in keeping with the OECD’s definition where trust is “holding a positive perception about the actions of an individual or an organization” (OECD 2017, p. 16). We also recognise the notion of trust as a psychological contract between the individual and the organisation as “expectations and obligations” (Cullinane and Dundon, 2006; Rousseau, 2001); and, the broader notion of trust as a social contract between government and citizen involving rights and obligations which has commanded the attention of political philosophers since the 17th century from Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, to Rawls and Gauthier, amongst others. We hypothesize that we can abstract from these overlapping definitions various micro-psychological contracts between government and citizen that encompass expectations of service culture, quality and obligations and entitlements of citizenship.

We hypothesize that in combination, trust comprises of various micro-psychological contracts between government and citizens that encompass expectations of service culture, quality and obligations and entitlements of citizenship.

It is important to recognize the three different components of trust that operate in a liberal democracy:

- Trust occurs when A trusts that B will act on their behalf and in their interests to do X in particular and more generally.

- Mistrust occurs when A assumes that B may not act on their behalf and in their interests to do X but will judge B according to information and context. This definition is associated with the notion of a critical citizen and active citizenship and is viewed to strengthen democracy.

- Distrust occurs when A assumes that B is untrustworthy and will cause harm to their interests in respect of X or more generally.

In contrast to mistrust, distrust is viewed to weaken democracy and confidence in government.

For the purposes of this study, this would mean that public trust in government services is earned by agencies delivering on the service promise in a way that values and respects citizen input. Given this understanding, for this study trust is defined as “A citizen’s belief that [the institutions of government] fulfil their mandates with competence and integrity, acting in pursuit of the broader benefit of society” (OECD, 2017, p. 23).

What’s going on? Supply and demand-side theories of political trust

How you tackle the problem of declining trust depends upon how you define the problem, and our data and review of the international literature demonstrate that the problem is multi-dimensional requiring a broad range of responses. The literature can be organised loosely around demand and supply-side theories of trust.

Demand-side theories focus on how much individuals trust government and politics and explore their key characteristics. What is it about citizens (such as their educational background, class, location, country or cohort of birth) which makes them trusting or not? What drives the prospects for political engagement, and what makes citizens feel that their vote counts; or, that their active engagement could deliver value? In general, the strongest predictors of distrust both in Australia and internationally continue to be attitudinal and are connected to negativity about politics experienced in different ways by different groups of citizens depending upon their social and economic circumstances, and the perceived relative power of their political voice.

It is therefore unsurprising that the most marginalised members of our society are embedded in disadvantaged communities and are the most distrusting of government services. Demand-side interventions therefore focus on overcoming various barriers to social, economic or political participation through improved civic or adult education, labour market activation, public participation, and improved representation of marginalised groups, and other forms of institutionalised citizen empowerment.

Supply-side theories of trust start from the premise that public trust must in some way correspond with the trustworthiness of government. The argument here is that it is the performance (supply) of government that matters most in orienting the outlooks of citizens, together with its commitment to procedural fairness and equality. Interventions on the supply-side therefore seek to enhance the integrity of government and politicians, and the quality and procedural fairness of service delivery or parliamentary processes through open government or good governance. This includes mechanisms of transparency and accountability, enhancing public service competence and adopting anti-corruption measures. Performance legitimacy comes from the public’s assessment of the government’s record in delivering public goods and services like economic growth, welfare and security (Boswell 2018). If important, as commonly assumed, then public confidence should relate to perceptual and/or aggregate indicators of policy outputs and outcomes, such as satisfaction with the performance of the economy or the government’s record on education and healthcare.

Procedural legitimacy focuses on the way that officeholders are nominated to positions of authority through meritocratic processes, and the mechanisms of accountability for office-holders, and whether citizens feel that these processes and mechanisms are appropriate, irrespective of their actions and decisions (Tyler and Trinkner, 2017). These issues of performance legitimacy also extend to the construction of representative politics, and the way that representative institutions work and operate in terms of the conduct of the business of government (see Alonso, Keane and Merkel, 2017).

We argue that, since it is beyond the decision-making authority of the APS to address the problem of declining public trust with politicians, it makes more sense to focus our attention on how the APS can deliver the best service experience possible and contribute to bridging the trust divide. This draws us inexorably towards particular supply-side theories of trust which focus on enhancing the quality of public service production. Trust in public services matters because this is where citizens interact with government and an opportunity is provided for strengthening the quality of democratic governance. Intuitively, public service design and delivery should be a fertile space for trust building.

Why trust and distrust matter

If social trust captures relations between citizens, political trust goes more directly to the issue of whether citizens trust their political leaders, when in government, to do the right thing and as Donald Kettle (2017, p. 1) puts it, “keep their promises in a just, honest, and efficient way”. There is widespread concern among scholars and in popular commentary that citizens have grown more distrustful of politicians, sceptical about democratic institutions, and disillusioned with democratic processes or even principles (see Dalton, 2004). Weakening political trust is thought to erode civic engagement and conventional forms of political participation such as voter registration or turnout (Franklin 2004), to reduce support for progressive public policies (Van Deth et al., 2007) and promote risk adverse and short-termist government (Hetherington, 2005), and to create the space for the rise of authoritarian populist forces (Norris and Ingehart, 2018). Also, there may be implications for long-term democratic stability; liberal democratic regimes are thought most durable when built upon popular legitimacy (Almond and Verba, 1963).

The risks of democratic backsliding are regarded as particularly serious if public scepticism spreads upwards from core institutions of governance to corrode citizen perspectives about the performance of liberal democracy and even its core ideals (see Diamond and Plattner, 2015; Mounk, 2018; and, Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018). Others counter that the picture should not be exaggerated, as anxiety about public trust in government usually ebbs and flows over the years (Norris, 1999 and 2011).

In many discussions, it is often naively and automatically assumed that any erosion of social and political trust among citizens is inherently problematic, as it reduces the incentives for cooperation. The Australian case is distinctive also in the sense that it is unusual to see such a crisis in political trust when the economy is performing so well. Despite an extensive period of economic growth, the majority of Australians have little faith in the system of government being able to do anything about the big problems in their lives or those facing society more generally. Declining political trust undermines public confidence in the ability of government to perform its core tasks and address the big public policy problems of our times (Stoker et al., 2018b). It impacts negatively on social cohesion at a time when we need more integrated communities (Miranti and Evans, 2017) and, makes it more difficult for Australia to lead on key geopolitical issues and champion liberal democracy when it is under threat globally (OECD, 2017).

In sum, trust is integral to effective government. It is the ‘glue’ that enables collective action for mutual benefit; without trust our ability to make social progress is constrained severely. Arguably trust is even more important in a federated state where collaborative problem solving is fundamental to maintaining nation building efforts.

But where can we conceptualise trust in government services in this space? Intuitively, political trust can impact positively or negatively on public perceptions of the quality of public service delivery. At the same time, trust in government services could also impact positively or negatively on political trust or other dimensions of trust such as social trust or public confidence in government. Whether there is a significant relationship between these variables is an empirical question and one that we will pursue in our empirical research.

What do Australians think about the services they receive?

Base-line findings from the Citizen Experience Survey undertaken by the Department of PM&C indicate that despite similar satisfaction rates with public services as urban citizens, and similar levels of effort to access and receive public services, only 27 percent of regional Australians trust Australian government public services, compared with 32 percent of urban citizens. These low levels of trust, despite high levels of satisfaction, highlight that government performance (where here trust in public services is a proxy) is only one factor driving citizens’ confidence in government (Sims, 2001). Rather, government performance – and with it citizen trust in public services, trust in government and trust in democracy – is the result of complex interacting processes which reach beyond service delivery, including: policy and program design which attempts to reconcile diverging interests and balance numerous political and resource constraints, media framing of government performance, and, the behaviour of political elites (Sims, 2001; Stoker et al., 2018b).

Do Australians have preferences in terms of how services are delivered?

We only have national data on this issue; therefore, we will explore this issue in our focus group research. There is a sustained willingness amongst the Australian citizenry to use online services and a preference for online services over other delivery channels in simple transactional service areas (Evans and Halupka, 2017); however, evidence from the Department of Human Services (Senate Estimates July 2018 to February 2019) suggests that “face to face” channels remain the most effective driver of citizen satisfaction especially for more complex services. It is evident that the mix of channels is important to respond to the different needs of citizens. As Carter and Belanger (2005) observe these factors inform the trustworthiness of e-government services and influence broader service uptake; citizens need to trust both the agency and the technology (Lee and Turban, 2001).

What do regional Australians perceive to be the barriers to service delivery?

The data presented in sections three and four of the report are useful in terms of helping us to identify potential barriers to the take-up of public services. It draws on findings from the secondary literature on regional Australia. Here we use Sabatier’s (1986) seminal model of the implementation gap to identify potential cognitive, environmental and institutional barriers to the delivery of government services in regional Australia to organise evidence from the secondary literature (see Figure 2).

Cognitive barriers refer to obstacles to the capacity of the APS to understand the service needs of Australians citizens and respond to the needs and aspirations of local communities. Institutional barriers refer to organisational issues, largely linked to resources of different kinds (e.g. financial, knowledge, target group political support) which impact on the capacity of public agencies to create and deliver quality public services.

Environmental barriers refer to exogenous factors which can undermine the capacity of public organisations to create and deliver quality public services. Most environmental factors are beyond the control of service providers but need to be factored into strategic thinking particularly in areas of risk-management. These can include issues such as socio-economic and environmental conditions, and support from federal, state and local politicians and media.

The most significant sources of slippage in service delivery reported in the broader implementation literature tend to arise from six main sets of institutional factors[5]:

- Ambiguous and inconsistent service objectives;

- Inadequate causal theory of change and understanding services as a means to an end and not an end in themselves;

- Failure of the implementation process to ensure compliance because of inadequate resources, and/or inappropriate policy instruments;

- The discretion of street-level bureaucrats and the recalcitrance of the implementing officials;

- Lack of support from affected communities and relevant government agencies;

- Unstable and uncertain socio-economic contexts which undermine either political support and/or the causal theory.

Here, issues of environmental context and how services are designed and implemented come into sharp focus, which is explored empirically in this study.

Cognitive barriers

- Community perceptions of being left behind (rural realism)

- 'Top-down' approach to policy and service design

- Negative perceptions of Federal government

- The long time required to foster community acceptance

- Extent of behavioural change required

Environmental barriers

- Social isolation

- Public support

- Support of local media

- Socio-economic conditions and technology

- Attitudes and resources of constituency groups

- Support from federal, state and local politicians

- Commitment and leadership skills of implementing officials

Institutional barriers

- Unsympathetic service culture

- Unclear and inconsistent objectives in service delivery

- Incorporation of adequate causal theory of change

- Adequate allocation of financial resources

- Hierarchical integration within and among implementing organisations

- Inflexible decision rules of implementing agencies

- Recruitment of front-line staff with adequate skills/training

- Challenge of managing confidentiality in small communities

- Technical support

- Access to appropriate service providers and advocacy groups

Stages in the service delivery process

- Outputs of implementing agencies

- Compliance with policy outputs by target groups

- Actual impacts of policy outputs

- Perceived impacts of policy outputs

- Major revision in policy

Figure 2. Barriers to service delivery in regional Australia[6]

How can the APS improve service delivery?

Our review of the public management literature suggests that there is an emerging understanding of the constituent elements of a better practice service delivery framework that is applicable to both urban and regional settings. The most common supply-side elements that are used to build an effective service delivery framework include:

- Service culture – normally directed by the host Department’s strategic vision and delivered through its leadership principles, APS values, business processes and performance framework. Once a service delivery system and realistic service level agreements have been established, there is no other component more integral to the long-term success of a service organisation than its culture.

- Organisational capacity and capability - even the best designed processes and systems will only be effective if carried out by organisations with the capacity, and people with the capability, to deliver. Organisational capacity and capability are key determinants of service excellence. In cases where services are augmented through forms of collaborative governance with States, territories or the community sector a focus needs to be placed on evaluating the quality of collaboration.

- Service quality – includes strategies, processes and performance management systems. The strategy and process design is fundamental to the design of the overall service management model.

- Service experience – is a little trickier as it involves both demand and supply-side interventions – the latter involves user intelligence, account management and continuous improvement and the former works on the basis that the user/stakeholder is part of the creation and delivery of the service and then designs processes built on that philosophy – this is called co-creation or co-design.

- Service innovation and forward thinking – is a supply-side intervention and ensures that the organisation has access to a strong evidence base on what works and has developed innovation systems to allow it to build effective knowledge networks to co-create new service products to stay ahead of the game.

By implication, this study explores whether these five elements are integrated effectively within current service systems and achieving ‘line of sight’ between goals, policies, programs, services and their achievement (see Lissack and Roos, 1999).

Conceptualising trust in the context of public service delivery in regional Australia

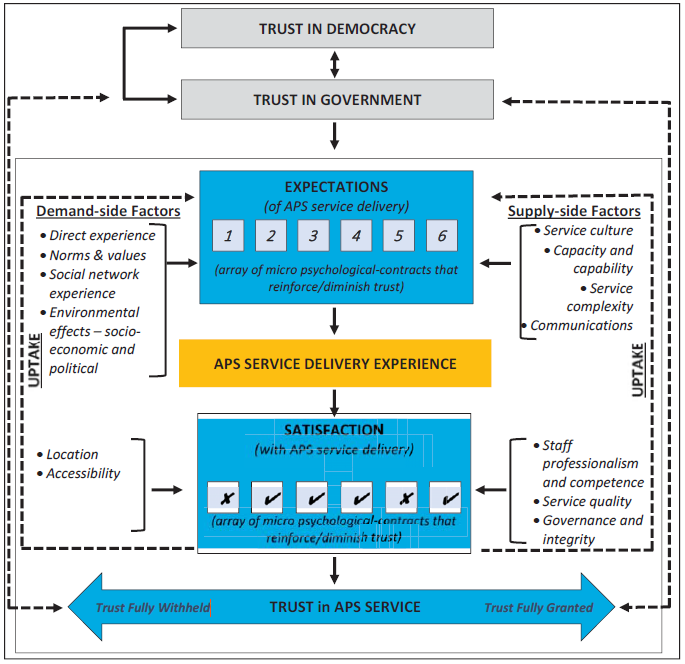

This rapid review of selective academic and practice-based literatures has helped us to establish the constituent elements of an analytical framework for identifying the drivers of trust in government services and, by implication, the barriers and potential enablers to service delivery. As Figure 3 illustrates, we hypothesize that public trust in government services is driven by a combination of demand and supply-side factors that shape service expectations and satisfaction.

The critical demand-side factors include citizen perceptions derived from direct personal and network experiences of service provision. These perceptions are also informed by socio-economic, political and environmental factors. The critical supply-side factors include citizen perceptions of the service culture, organisational capacity and capability and experience.

These demand and supply-side factors can be understood as a series of micro-contracts between government and citizen that either undermine or promote trust in government services depending on the quality of service provision and the changing environmental context.

Footnotes

[5] See Dunleavy 2010; Halligan 2011; Hill and Hupe 2003; Hupe 2017; Newman 2005; Peters 2013; Redell 2008; Schofield and Sausmann 2004.

[6] This is an interactive model in the sense that these sets of variables do not exist in a vacuum; they interact in complex and often unexpected ways.