Recommendations: “Citizens not customers – Keep it simple, say what you do and do what you say”

Key recommendations:

- Achieve ‘line of sight’ - between policy, programmes and services around the first principle of integrating program management and delivery functions through regional service centres.

- Citizen-centred service culture – introduce a ‘user-first’, ‘co-design’ approach for all services and a personalisation approach with strong advocacy capability for citizens experiencing complex problems. Citizens stress the need for greater client care and support.

- Capacity, communication and capability – enhance service culture capability, greater advocacy support for the vulnerable and intelligent marketing and communication of government services through targeted channels (strategic communication and engagement).

- Service quality – establish a single source of truth across government information and reduce the complexity of the service offer.

- Service experience – introduce a ‘tell us once’ integrated service system which values the time of the citizen and understands and empathises with their service journeys.

- Citizen-centred service innovation – an opportunity for innovation lies in digital access and support; the creation of integrated regional service hubs; the recruitment of “trusted” and “local” community service coordinators; and viewing complaints as learning opportunities.

The following recommendations do not represent a commitment by PM&C or the Australian Government to change but have been distilled by the research team for further exploration by the APS. The recommendations have emerged from three sources: interviews with APS leaders, focus groups with Australian citizens and a co-design workshop convened with core stakeholders to translate the research findings in a meaningful way for practice. The recommendations correspond with the key findings that emerge from this research as reflected in the subtitle of our report – “Citizens not customers, keep it simple, say what you do and do what you say”.

We argue, in concluding this report, that public services can be a critical space for trust-building between government and citizen but this requires development of citizen-centric service models that place the language of the citizen at the centre of service culture, design and delivery and embrace the mantra – “Citizens not customers – keep it simple, do what you say and say what you do”. “Citizens and not customers” because the notion of citizenship builds trust. It helps establish a trust system between government and citizen that is based on parity of esteem and creates common ground for transactions to take place. In contrast, given imperfect access to resources, customers are inherently unequal and potentially a force for distrust.

There are at least two other differences in the use of the concept of the citizen and the customer that are germane to our discussion. First, the customer is self-regarding –he/she largely choose what is best for themselves in the marketplace. In contrast, citizens regard others and particularly the needs of society – they choose what is best for society. Or at least they choose their perception of what is best for society. Citizens possess individual rights but recognise their obligations to the community. Second, citizens have broad ownership of the problems of society and have a common responsibility for fixing those problems. Customers expect those problems to be fixed for them. Hence, citizenship is potentially an empowering force and the customer a disempowering one.

A common argument against using the concept of citizen is the claim that many of the people the APS provides services for aren’t Australian citizens. This argument is problematic both from an international legal perspective and because of the issues outlined above with the alternatives. All visitors and residents (temporary or permanent) in Australia enjoy different rights and gradations of citizenship even if they are not full citizens because Australia is a signatory to a range of international laws that ensure equal treatment (including for children under the UN Charter) and has a number of bi-lateral agreements with individual countries that extend certain rights. For example, British tourists have certain healthcare service and working visa entitlements that are reciprocated for Australian citizens in the United Kingdom. In short, the APS serves different types of citizen.

Meeting citizen expectations inevitably requires both a better understanding of the service needs and aspirations of an increasingly segmented citizenry and a service culture that see’s like a citizen and not a customer.

As noted in Section Five, the degree of common ground between citizens and APS leaders on the enablers to a higher quality service experience is remarkable and this has also proven the case with our workshop participants. This has helped us to clarify six iterative and potential pathways to reform for further exploration. These largely align with the constituent elements of the best practice service delivery framework presented in Section Two and Appendix 1.

Achieve ‘line of sight’ between policy, programs and services around the first principle of integrating program management and delivery functions through regional service centres

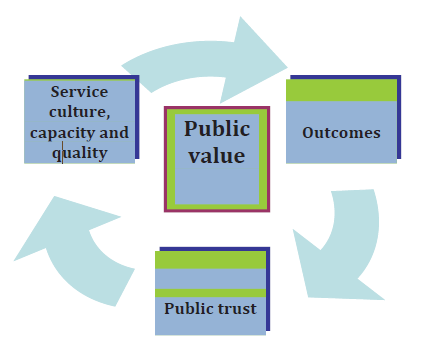

‘Line of sight’ is achieved when there is a clear accountability route between delivery in the community (outcomes) and the high-level goals the agency has set itself (see Figure 8).[10] The evidence here clearly demonstrates that public services are a creative space for building trust with the citizen but there appear to be systemic barriers to the achievement of ‘line of sight’ in practice. Two key strategic questions come to the fore. What can an agency do to achieve ‘line of sight’, lift performance and link Canberra better to the front-line and the front-line better to Canberra? And, what can the entire APS do (more generally whole-ofgovernment) to achieve line of sight, lift performance and link Canberra better to the frontline and the frontline better to Canberra?[11]

The development and implementation of a common service delivery framework for APS agencies with service delivery functions such as this one would be a useful starting point. This would also require an outcomes-based approach which is generally considered more likely to motivate those who will achieve the results sought: frontline workers and citizens themselves. This is the key to lifting service performance.

One of the difficulties with performance targets is that if they are not linked explicitly to outcomes through line of sight they can create a culture that works exclusively to meet targets without regard for the broader goals and the system in which government operates, resulting in the phenomenon of hard working organisations which achieve targets in the short term but which achieve less and less over the long term. By re-focusing on a small number of measurable and verifiable outcomes in different areas of policy endeavour, agencies can stay motivated on making progress.[12]

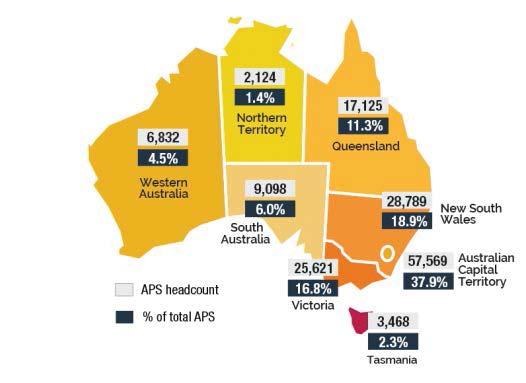

Then there is the question of how APS delivery agencies can achieve the degree of service integration that citizens would like to experience. The APS’s significant regional footprint provides rich opportunities in this regard (see Figure 6.2).

This could include the development of a regional institution aimed at:

- enhancing community engagement and inclusion;

- improving service culture; and

- achieving service integration (e.g. Services Australia Regional Service Centres).

Services Australia Regional Service Centres could have the following features:

- a hub and spokes partnership model with shared risk and investment across sectors;

- based at the regional level with spokes into local governance;

- operate on a place-based approach;

- a co-design approach would be deployed to ensure regional and community ownership;

- focused on delivering key well-being outcomes through a user-first approach with a mandate to upskill regional communities; and,

- through which APS services could be integrated through a whole-of-government approach.

Alternatively, Regional Support Centres could be organised around the implementation of regional programs aimed at addressing specific regional problems in social and economic sustainable development but using the same operating features. Victoria’s “Collaboration for Impact” provides a useful model in this regard.[13]

It should be recognised, however, that this would a radical departure from orthodoxy for many APS agencies. Australian public servants are measured and rewarded for success in refining processes (for instance, better consultation, less regulation, the monetisation of benefits), or for helping to produce outputs (more nurses, more qualifications achieved, more sustainable businesses) or for managing inputs (a bigger budget for recycling, a 10 percent saving in administrative costs) but are very rarely, if at all recognised for the contribution they make to achieving outcomes. So, there will be significant implications for performance measurement and management arising from this recommendation. Regardless of the model, permanence and cultural authority within the broader system of Australian governance will be important to avoid past failures.

It was also observed by our workshop participants that there is the potential here for savings. There is considerable waste and duplication within the existing siloed system; but, it has never been properly costed suggesting the need for the Department of Finance to undertake a productivity review of the existing service delivery system.

The budgetary system will also need to be refined to encourage greater collaboration between service delivery agencies. One way of achieving this would be for the Expenditure Review Committee to only accept collaborative New Policy Proposals from service delivery agencies.

The New Zealand Government has been much lauded for achieving significant progress in this area, firstly in consequence of reforms to cope with the Global Financial Crisis and then latterly to ensure more agile, and responsive service delivery.[14] The latest Kiwis Count Survey shows New Zealanders have increasing trust in the public service with satisfaction with the provision of services at a record high.[15] The New Zealand case should be closely monitored for progressive lessons.

Establish an authentic ‘citizen-centred’ service culture

What we do know from our findings is that citizens expect a ‘user-first’ approach for all the services they receive which recognises and understands their personal journeys through the service system. With greater complexity in certain service offerings citizens also expect a more personalised approach with greater client care and support. The APS is making more substantial progress in understanding how to proceed in this area given the path-breaking work of the ATO, DHS, and the DTA, and the investment in design and innovation units, practice guilds and user-simulation labs, whole-of-Commonwealth government.[16]

Continued support to foster this community of practice, encourage a multi-disciplinary approach and stimulate whole-of-government learning remains crucial.[17] With the support of the DTA we would envisage Regional Support Centres developing capability in human-centred design to ensure the delivery of usercentred services.

So, what could a high quality ‘citizen-centred’ service culture look like? Our focus group participants have given us a strong sense of the four value-based components of trust that they believe inform public trust in Australian public services:

- Integrity – procedural transparency and fairness, competence, consistency of information, advice and treatment

- Empathy – duty of care, respect and understanding

- Delivery – that the service promise will be met

- Loyalty – an expectation of ongoing support and guidance

These components of trust can be considered micro-psychological contracts between government and citizens and are the key to building service culture. As such, they should be modelled as public service delivery values. Above all, public trust in government services is earnt by delivering on the service promise in a way that values and respects citizen input.

Training programs should be co-designed with frontline staff and citizens to ensure that these four public service delivery values are embedded in practice. Service culture is achieved by people, not by structures or processes. Therefore, we need frontline public servants to want to understand the service delivery strategy, to want to keep it relevant and effective, and who see how their work supports the strategy. There is much evidence that people at the frontline tend to have their own ideas about what they are supposed to achieve[18]. Part of being a strategic organisation rests in finding ways of creating an appetite for strategic working and in aligning the ways that people work at the front line (and of those in the wider community who co-produce outcomes) with the broader strategic goals of the APS.

Build APS capacity in strategic communication and service capability

The achievement of these new ways of working will require new/bolstered capability in areas such as strategic marketing and communication of government services, service advocacy for vulnerable groups, hard and soft service delivery skills, and community engagement.

It appears that much work needs to be in this area suggesting the need for a capability review to ensure that Services Australia Regional Support Centres are fit for purpose.

Ensure consistent levels of service quality

We have a strong message from citizens to “keep it simple, say what you do and do what you say”. Our data is very clear in establishing a causal relationship between complexity and declining trust, satisfaction and confidence. The argument that “the legislation is complex so the service is complex” does not sit easily with the citizen. This is viewed as a public service pre-occupation and an excuse for poor delivery.

The way forward inevitably requires establishing a ‘single source of truth’ across government information, and, reducing the complexity of the service offer, wherever possible. This will require authorisation to exchange and share information between agencies and with the private and community sectors.

Enrich the service experience

Once again our evidence is quite clear on what needs to be done to enrich the service experience: embed the four value-based components of trust in public service culture, adopt a user-first approach and introduce a ‘tell us once’ integrated service system which values the time of the citizen and understands and empathises with their service journeys.

‘Low hanging fruit’ solutions to enhance the citizen experience could include:

- introduction of greater transparency in setting service expectations from the outset;

- online tracking of service processes available to the user, with timeframes to achieve milestones;

- plain English explanations of the service promise;

- the redesign of application processes for simplification using user-design approaches; and,

- changing the channels of information delivery to focus on target demographics.

Citizen-centred service innovation

The pursuit of citizen-centred innovation is a condition for sustaining continuous improvement in the service system. The creation of Services Australia Regional Support Centres will provide an ongoing opportunity for innovation in areas such as community engagement, digital access and support, the design of collaborative forms of regional governance, the recruitment and development of “trusted” and “local” community service coordinators, and, a practical opportunity to convert complaints to learning and innovation opportunities at the regional scale.

This will require the institutionalisation of innovation and challenge. One of the greatest weaknesses in government is that basic assumptions too often go unchallenged. The most innovative companies in the private sector encourage challenge to the received way of doing things. They often employ people not for their manifest desire to conform, but for their potential to offer new ideas, to develop new products, for their ability to ‘shake things up’. More established corporations inevitably develop settled hierarchies and systems in much the same way that the civil and other public services do; but larger corporations often find ways of ‘institutionalising’ challenge, for instance by experimenting with new markets, goods or services through wholly-owned subsidiaries which are left to thrive or sink on their own. Success leads to the adoption of new approaches by the parent firm; failure to (usually) controlled financial losses, and possibly a search for new jobs by those responsible for those losses.

The public sector does not tend to work in this way. In part this is because experimenting with services that are mandated by elected political leaders and on which citizens might depend is unacceptable. The public sector also tends to shy away from challenge and innovation because its norms are of compliance not challenge, and its rewards are for the management of processes and of inputs and outputs, not for outcomes and achievements.

One way that we think government can encourage challenge is institutional. It can emulate the practice of the private sector by ‘ring-fencing’ challenge functions, for instance by setting-up shadow boards in organisations or service peer review in which service agencies provide developmental feedback to one another or where cross agency task forces are created to solve common delivery problems [19]. Another way is to systematise reward for innovative thinking. Instead of systems of annual review that reinforce behaviour that is compliant, orthodox and which successfully manage processes at the input/output level of operation, government and the wider public sector needs to actively reward results, however they are achieved.

Future research on trust in government services

Our sample of APS leaders made several recommendations for the future development of the Citizen Experience Survey. As previously noted, all agreed that there was a need for an ongoing Citizen Experience Survey underpinned by a standard whole of APS methodology and administered by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet but thought that this could be supplemented at the agency level with specific service surveys to boost sample size and allow for innovation in areas of particular concern to specific agencies.

In addition, there are at least seven important gaps in our knowledge of the present APS service system in regional Australia that require consideration:

- The findings of this research are not new, many of these barriers and enablers have been identified over recent decades, although this comprehensive focus on regional citizens does provide novel insights. Given that we have known these challenges for some decades, why has more change not materialised? More research is needed to better understand disconnections in line-of sight whole of Commonwealth government and between jurisdictions and the community sector. What is constraining positive changes in service delivery?

- There is a lack of coherence around the common purpose, principles and operational parameters governing the present APS service delivery framework. The data reported here demonstrates that staff both anticipate and expect change and they believe a culture shift is looming through the launch of both Services Australia and the APS Review. In the main, morale is fairly good (with some outliers) but a sense of uncertainty about the future is palpable and there are diminished levels of trust between policy owners, program managers and service providers. In sum, the present governing context provides an opportune time for change.

- We have no data on the views of street level bureaucrats on the strengths, weaknesses and future development of the present service system and yet we know from existing literature that service innovation largely emerges from the frontline.

- Despite significant public investment over the past decade, we also have limited evidence on what works in terms of regionally and rurally-based governance structures for coordinating citizen-facing services.

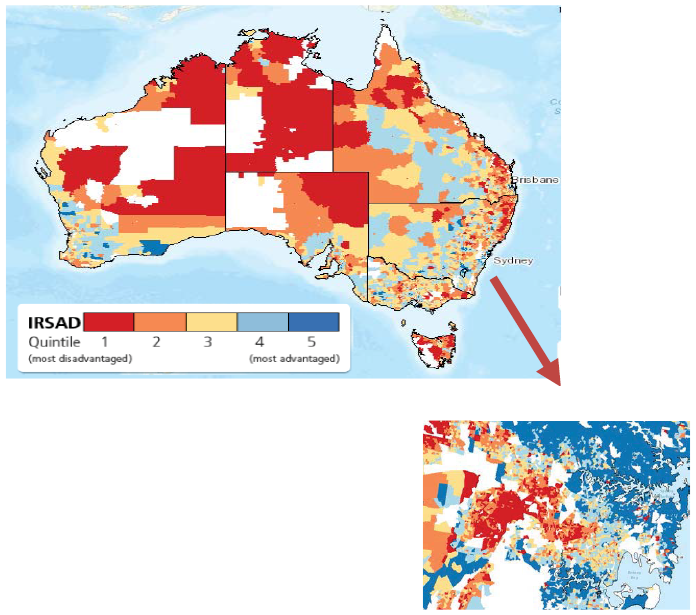

- We also have limited geospatial mapping of existing service and program delivery. Developing the ability to understand what is being delivered into a community by postcode (or other relevant spatial measure) would provide a powerful planning and decision-making tool. For example, we could use this to map under and over-supply of services in relation to the SEIFA index (see Figure 10).

- At the core of this change process is the need for better collaborative practice and yet our understanding of what this looks like in practice is limited. A research-practice program could be established to identify and share best-practice collaboration principles.[20]

- We have limited knowledge about the costs of delivering a siloed approach versus an integrated service approach suggesting the need for the Department of Finance to undertake a productivity review of the existing service delivery system.

- These are significant gaps in the evidence base that, if bridged, could enable better decision-making on regional service delivery problems and solutions.

Footnotes

[10] See: Evans, M. and McGregor, C. (2018), Mandate for change: Towards an integrated service delivery model, Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, for an attempt to achieve this approach in the APS.

[11] See: Productivity Commission New Zealand (2017), Measuring and Improving State Sector Productivity, Issues Paper, July 2017; PwC (2013), Improving public sector productivity through prioritisation, measurement and alignment, December.

[12] See Jake Chapman’s work on the use of targets, notably in: Chapman, J. System Failure: why governments must learn to think differently. London. Demos. 2002 and Bentley T and Wilsdon J (Eds). The Adaptive State. London, Demos, 2003.

[13] See: https://collaborationforimpact.com/impacting/initiatives/ (retrieved 20 November 2019).

[14] See: https://ssc.govt.nz/our-work/reforms/ (retrieved 20 November 2019).

[15] See: https://ssc.govt.nz/our-work/kiwis-count/ (retrieved 20 November 2019).

[16] See: https://www.dta.gov.au/blogs/digital-practice-guilds-government (retrieved 20 November 2019).

[17] See: Boddy, J. and Terrey, N. (2019), Design for a better future, Routledge.

[18] See Lipsky, M. (1980), Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York. Russell Sage Foundation..

[19] The Wales Assembly Government has a ‘shadow board’, although its role is primarily to air issues and offer alternative perspectives to the main management board (and to encourage staff development) rather than to explicitly challenge organisational assumptions.

[20] See: Evans, M. (2019), Discovery Report: Building a culture for change: from “collegiality” to “collaboration”, A joint submission from AusIndustry, Strategic Policy, Economic and Analytical Services and The Science and Commercialisation Division, Department of Industry, Innovation and Science and Evans, M. (2018), Methodology for Evaluating the Quality of Collaboration, Canberra, IGPA.