The view from the top: Insights from APS thought leaders

APS leadership perspectives on the barriers and enablers to public service production

We interviewed a group of prominent APS thought leaders on how the APS could use the public service experience as a space for trust building. Informants were selected on the basis of their portfolio and track record in delivering high quality programs and services to Australian citizens, and engaging in service innovation. Informants were asked to review the key observations emerging from the Citizen Experience Survey and to reflect on the implications of the findings (see Box 10).

Box 10. Key observations from the Citizen Experience Survey

- Satisfaction (52%) with Australian public services is higher than trust (31%).

- Trust is significantly lower in regional (27%) in contrast to urban (32%) areas.

- Personal individual service delivery experiences drive overall trust.

- Perceptions of transparency affect trust.

- Service experience during significant life events affect trust in the APS.

- Citizens and/or residents who were born overseas have high levels of trust.

- Participants could not establish an independent view of the APS; they just see government.

- The APS can improve elements of service-delivery to drive higher levels of trust.

- The evidence points to the need to build collaboration across the APS, enhance service delivery reform, and ultimately, drive tailored responses that reflect the voices of Australians.

“What worries me is we keep on knowing what the problem is, we keep on articulating it and why are we not doing anything about it? That’s what worries me. So my question is, have we sufficiently articulated the barriers from a bureaucratic perspective to actually make change? We seem to know what the problems are but we actually don’t get out on the ground and try to do real solutions when we need to (KS8).”

APS leaders were not surprised by the results of the Citizen Experience Survey but did identify several mitigating factors that need to be taken into account in any response. First, constitutionally the APS cannot address the problem of declining political trust and by implication the perceived poor performance of politicians; although it evidently impacts on public perceptions of the quality of public service delivery. The focus of the APS effort should therefore be on improving the quality of service delivery; a task within the APS’s domain of responsibility. Second, citizens are less likely to trust services that form part of government policies that they disagree with; hence you will never be able to please everybody. Third, Australians have high expectations of service delivery that might be difficult to meet given budgetary constraints. They expect to have the same quality of experience with public and private sector service providers. It is therefore important to establish a public expectation thesis, i.e. given prevailing constraints what could the service provider reasonably be expected to achieve? Fourth, accessing complex services requires significant citizen effort due to legislative requirements, which is likely to lead to diminished trust. And, fifth, many services that Australians receive are in David Thodey’s terms “seamless” and “invisible” (e.g. PBS, Medicare) but, because they do not involve formal evaluation touch-points, go unrecognised by the citizen.[9]

Barriers to the delivery of high-quality government services

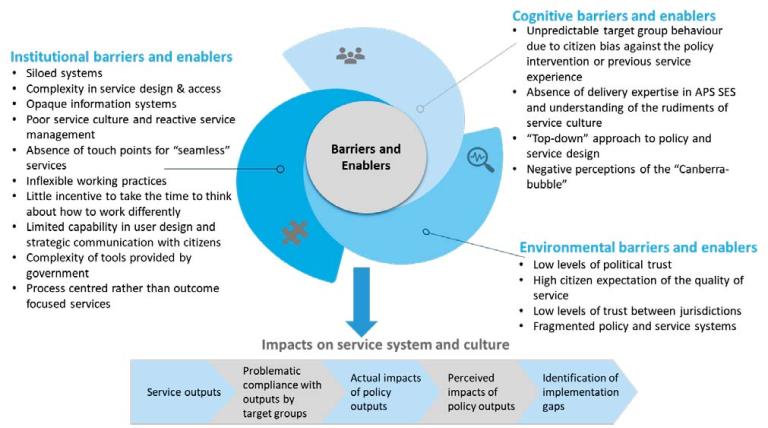

Figure 7 provides an overview of APS leaders’ perceptions of the key barriers to the delivery of high-quality government services. These have been organised around cognitive, institutional, and environmental barriers. Cognitive barriers refer to obstacles to the capacity of the APS to understand the service needs of Australians and deliver on the service promise.

“To build trust we need to actually engage with people and businesses that consume services from government in the way that they think about services rather the way we're organised in government.” [KS2]

“At the end of the day, it can’t get much worse, it can only get better. And until they put some normal people in that actually know what it’s about that I suppose, for argument’s sake, a normal person, not one that sits behind a big oak desk and whatever else and has actually had experiences, that have had drought experiences and aged care experiences and [Financial Support Service] experiences, whatever, those people, they are the ones that can actually try and change it for the better because they’ve actually been there, done that, not sit behind a desk and let some other puppet do all their work for them.” [FG5]

Institutional barriers refer to internal organisational issues which impact on the capacity of public organisations to create and deliver quality public services. The key institutional barriers to delivery identified by APS leaders include: siloed systems that are not conducive to service delivery; complexity in service design and access; difficulty in finding the right information, at the right time, in the right context; reactive service management; poor communication with users about entitlements and obligations; users being required to provide information multiple times; and, the complexity of tools provided by government.

“I think without exception the user journey approach is being accepted within agencies. A really strong desire to understand how to do collaborative delivery is also strongly supported. We have a community of practice, we have guilds, we have training and development programs that are proving to be very popular across the APS. I think the thing that is most challenging though, is as we think about user experience it invariably spans agencies, and layers of government.” [KS2]

Environmental barriers refer to exogenous factors which can undermine the capacity of public organisations to create and deliver quality public services. Most environmental factors are beyond the control of public organisations but need to be factored into strategic thinking particularly in areas of risk-management and strategic communication to staff. In this instance they include:

- low levels of political trust;

- high citizen expectation of the quality of service;

- low levels of trust between jurisdictions; and,

- fragmented policy and service systems.

Most of these barriers can also be identified as conditions for high quality service provision. For example, if we consider the cognitive barriers in Figure 7 these involve:

- unpredictable target group behaviour due to citizen bias against the policy intervention or frustration with previous service experience;

- the absence of delivery expertise in APS SES and limited understanding of the imperatives of a service culture;

- a ‘top-down’ approach to policy and service design; and,

- negative perceptions of the “Canberra bubble” (the ‘tyranny of distance’).

Each of these barriers can be turned into a positive value if a transformational strategy is implemented to reverse prevailing conditions. For example;

- potentially can be addressed through improvements to the service culture;

- potentially can be addressed through recruitment of appropriate capability;

- potentially can be addressed through integrated policy systems and inclusive policy design; and,

- potentially can be addressed through better strategic communication and authentic community engagement and co-design.

These sets of barriers do not exist in a vacuum but interact with one another in complex and often unexpected ways. They provide a basis for strategic thinking about both the necessary conditions for high quality service provision and effective strategies for achieving them (refer Figure 2).

Enablers to the delivery of high-quality government services

Most informants argued that a culture shift was required in the way Commonwealth departments and agencies manage and deliver public services to meet the Thodey aspiration of “seamless services and local solutions designed and delivered with states, territories and partners”. Although many noted that a change process was underway in most agencies, four specific reform themes loomed large in discussion.

First, most of these APS leaders recognised the need for a whole of government approach to combat declining trust in regional and remote communities:

“The APS footprint can be used to facilitate whole of APS collaboration in community engagement (KS4).”

“The APS should be able to collaborate whole of government in policy design and delivery through shared accountability mechanisms and budgetary incentives (KS1).”

Three service delivery principles were emphasised by most informants: regional decentralisation; user-first design; and, personalisation supported by a strong service culture.

“Practice co-(user) design by default and use behavioural insights to improve our understanding of the needs and aspirations of target groups and develop personalised service offerings (KS6).”

“Develop opportunities for dynamic engagement with users through inclusive service design and strategic communication (KS5).”

For example, it was argued strongly that departments should see user feedback as an opportunity for progress; i.e. a problem-seeking culture should be fostered. All complaints should be taken seriously and considered at executive board level. Simulators should then be used to make progress (e.g. ATO simulation lab, DTA’s co-lab).

“Each and every SES officer needs to do service delivery, so they understand that their role in life is to service the citizens of Australia through the elected government of the time. So that’s what we’re here for, we should never lose sight, every single day we should never lose sight that were actually doing this for the greater good (KS6).”

Most significantly, it was observed by several respondents that digital should not be viewed as the cure-all for regional service delivery problems nor should we assume that citizens believe this to be the case either:

“I think that the opportunities for regional areas are exactly the same as anywhere else because the key thing is that digital is not the answer to everything, we always view it as part of a mix of different solutions which may be backend, it could be front-end service delivery – you know, that direct relationship or the interaction and transaction occurring between the customer service officer and the individual. The solutions may range so digital is always a part of, as opposed to the end in itself; and so therefore there will be particular context or situations where digital could be made use of in order to reach greater numbers of people in regional areas. But only when we deem it to be a useful part of the solution (KS9).

Public services as a space for trust building

The evidence from our interviews with APS leaders points to the need to build collaboration across the APS, enhance service-delivery reform, and ultimately, drive tailored responses that reflect the plurality of individual and community identities in Australia. The degree of common ground between citizens and APS leaders on both the barriers and enablers to a higher quality service experience is remarkable and helps us to clarify six pathways to reform (see Table 5).

- Achieve ‘line of sight’ - between policy, programmes and services around the first principle of integrating program management and delivery functions through regional service centres.

- Citizen-centred service culture - introduce a ‘user-first’, ‘co-design’ approach for all services and a personalisation approach with strong advocacy capability for citizens experiencing complex problems. Citizens stress the need for greater client care and support.

- Capacity, communication and capability – enhance service culture capability, greater advocacy support for the vulnerable and intelligent marketing and communication of government services through targeted channels (strategic communication and engagement).

- Service quality – establish a single source of truth across government information and reduce the complexity of the service offer.

- Service experience – introduce a ‘tell us once’ integrated service system which values the time of the citizen and understands and empathises with their service journeys.

- Citizen-centred service innovation – an opportunity for innovation lies in digital access and support; the creation of integrated regional service hubs; the recruitment of “trusted” and “local” community service coordinators; and viewing complaints as learning opportunities

Table 5. Barriers and enablers to quality service provision

| Delivery barriers | Service reform |

|---|---|

| Lack of proactive engagement from government with users | Personalisation of public services e.g. identification and ‘push out’ of relevant user services |

| Users experience difficulty finding the right information, at the right time, in the right context | Establish a ‘single source of truth’ across government information |

| Access to services is hindered by the complexity of government structures | Join-up, simplify and ensure ‘line of sight’; collaborations across agencies to enable holistic delivery/programs; more emphasis on partnerships with other levels of govt (or service providers) to leverage resources and enable improved outcomes |

| Users are uncertain about government entitlements and obligations | Proactive engagement from government through strategic communication |

| Public services are not meeting user service delivery expectations | Strengthen service charters and incentivise performance to improve delivery outcomes |

| Users are being required to provide information multiple times | Establish ‘tell us once’ – integrated service systems; digital advances, one-stop-shop, data matching opportunities to produce seamless services based on known data |

| Inconsistent and inaccessible content | Adopt user-first design principles |

| Complexity of tools provided by government | Simplify around user needs |

Footnotes

[9] Follow-up questions with our APS leaders included: what can the APS/your department do to help address these issues? Are there new capabilities and technologies that could make a difference? Are there other ways that the APS can help bridge the trust divide? And, how will the APS achieve David Thodey’s recommendation of “seamless services and local solutions designed and delivered with states, territories and partners”?