MPC Annual report 2017–18: Review of employment-related decisions

Reviews of action performance

The performance target for reviews of employment actions is that 75% of reviews will be completed within 14 calendar weeks of receipt of an application. The target for promotion reviews is that 75% will be completed within either eight or 12 weeks of the receipt of an application, depending on the size of the applicant field—that is, eight weeks for up to 10 parties and 12 weeks for 10 or more parties to a review.

We met our performance targets in the reporting year with 77.3% of review of employment action cases finalised within the target timeframe (77.4% in 2016–17). All promotion reviews were completed within the target timeframes.

We seek feedback through a survey of a sample of review of employment action applicants (once their application is finalised). In 2017–18 the response rate for the survey was 37% (32 respondents)*—this compares with an 18% response rate in 2016–17. The feedback shows that 53% of respondents found out about their review rights from their agencies. The next most significant source of information was the MPC website. The majority of respondents who used the website said it was easy to find the application forms.

The majority of respondents found the review information sheet provided to them after making their application to be the right length, contained the information they needed, and was relevant and easy to follow and understand.

Just under half of respondents (44%) reported dissatisfaction with their contact with the Office. Of these, 71% would have liked more information about the scope of the review and 43% did not think they received appropriate information about the review process. This suggests that at the beginning and throughout the review process we need to provide to applicants better information about the scope of their review and what they can expect to achieve.

Sixty-six per cent of respondents indicated that they understood the final letter or report they received from the Office. The remainder said they did not understand the report or letter. Their reasons included that their statements and views were not sufficiently taken into account or that they found the written reasons for the decision difficult to understand.

Thank you for completing, and sending, the secondary review findings. I appreciate your fairness, and attention to detail. The only comment I wish to make is that I appreciate your recommendation to the [agency] … However, if your recommendation leads [the agency] to improve its processes, and that leads to better outcomes for [employees in the same situation], then it was well worth seeking a secondary review.

– review applicant, November 2017

Respondents told us they would like more updates on the progress of their review, and most felt the review took longer than they expected.

Some of the survey responses suggested the need for improvements in relation to a number of procedures and practices. These matters will be incorporated in the strategic review we plan for the second half of 2018.

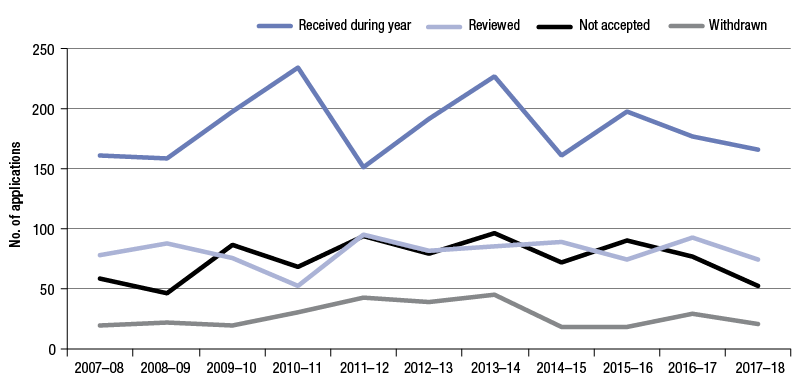

Figure M1 shows the trends in review casework in the past 11 years.

FIGURE M1: TRENDS IN REVIEW CASEWORK, 2007–08 TO 2017–18

Review casework

Table M1 in the appendix provides information on the number of applications for review (other than promotion review) received and reviews completed in 2017–18 compared with 2016–17.

In 2017–18 we received 166 applications for review in comparison with 177 in 2016–17. A total of 149 cases were finalised, including 23 cases carried over from 2016–17. Of the finalised cases, 75 were subject to a full merits review. The remainder were ruled ineligible for reasons set out in the next section.

In 2016–17 the Office finalised 76% of its review caseload—that is, cases reviewed and cases determined to be ineligible for review. In comparison, in 2017–18 we finalised 68% of the review caseload. This represents a decline in work activity. The reasons for this included: a staff member acting in the role of Merit Protection Commissioner; staff leave and movement; reallocation of resources to support a statutory inquiry.

The average time taken to finalise a case was 11.48 weeks (excluding time ‘on hold’)—well within the 14-week target. The total average time to finalise cases including time ‘on hold’ was 18.2 weeks.

Review cases are put ‘on hold’ when the review is not able to progress. This is usually because we are waiting for information or because of the unavailability of parties to the review. Time ‘on hold’ is not counted in timeliness statistics.

In 2017–18 on average 37% of the time between the date an application was received and the date the review was finalised was spent ‘on hold’. The average time ‘on hold’ for a finalised review decreased from 7.2 weeks in 2016–17 to 6.7 weeks in 2017–18. The main reasons for placing a case on hold are waiting for:

- papers or information from the agency—51%

- additional information from the applicant—30.7%

- an agency to make a sanction decision—9.4%.

An application for review of a decision that an employee has breached the Code of Conduct may be placed on hold pending receipt of an application for review of the sanction arising from the same matter.**

Delays originating in the Office, including the 10-day Christmas closure, accounted for 7% of the time cases were on hold.

Thank you so much for sending me the decision and the recommendation. It is a tremendous relief that people understand my circumstances. My apologies for the rushed nature of the request. Unfortunately circumstances beyond my control meant [the review application needed to be finalised quickly] … Thank you again to everyone involved for all of your hard work.

– review applicant, October 2017

Applications not accepted for review

In 2017–18, 28% of cases were not accepted for review compared to 35% in 2016–17. The reasons for not accepting applications varied according to the type of review.

The main reasons for not accepting applications for review of Code of Conduct decisions were:

- The application was made out of time.

- The application concerned decisions that were not determinations of misconduct or sanction decisions.

The main reasons for not accepting applications for review of employment action matters other than Code of Conduct decisions were:

- The application was about a matter that fell into one of the categories of non-reviewable actions set out in Regulation 5.23 or Schedule 1 to the Regulations—28%.

- The Merit Protection Commissioner exercised a discretion not to review a matter for various reasons, among them that nothing useful would be achieved by continuing to review the matter—25%.

- The application was out of time—19%.

- The applicant needed to first seek a review from their agency—17%.

Generally, decisions on applications for review that are not accepted are made quickly—over half in less than two weeks. Some decisions can take longer if the decision-maker needs to clarify matters of fact with the agency or the review applicant—17% took more than four weeks. The average time taken to decide to decline an application was just under three weeks.

Number of reviews by agency

Table M3 in the appendix details the number of reviews by agency. We completed reviews in 20 agencies. The Department of Human Services accounted for 52% of the completed reviews. The Departments of Home Affairs and Defence and the Australian Taxation Office together accounted for a further 23% of reviews.

Review outcomes

The Merit Protection Commissioner may recommend to an agency head that a decision be set aside, varied or upheld.

In 2017–18 we upheld 60% of agency decisions or actions in the 75 cases reviewed. This result is similar to that for 2016–17. In one-third of cases it was recommended that the decision under review be varied or set aside and a further 7% of cases resulted in a conciliated outcome.

Compared with other types of employment decisions, we are more likely to recommend that Code of Conduct decisions be varied or set aside. This year 38% of determinations of misconduct or sanctions reviewed by the Office (29) were set aside or varied compared to one-third of such cases in 2016–17. In comparison, we recommended that 24% of employment actions that had first been reviewed by the relevant agency (secondary reviews) be varied or set aside, compared with 18% in 2016–17.

I thank you for your professionalism, including courtesy (both features of which I’m unsurprised; the APS grapevine gives you high marks).

– review applicant, July 2017

Two reviews conducted under Part 7 of the Regulations related to findings that a former APS employee had breached the Code of Conduct. In one case, we recommended that the agency decision be set aside because of a procedural concern and, in the other, we recommended a variation to the elements of the Code the employee was found to have breached.

The following are the main reasons for recommending that agency misconduct decisions be set aside:

- Procedural problems in the decision-making process that result in substantive unfairness to the employee.

- The employee has not done what they were found to have done.

- The employee did what they were found to have done but it was not misconduct.

The main reasons for recommendation that agency misconduct decisions be varied are:

- The employee has done only some of what they were found to have done.

- The agency has misapplied elements of the Code of Conduct.

- The sanction is too harsh based on an objective assessment of the seriousness of the employee’s behaviour or because insufficient regard was had to mitigating factors.

The following are the main reasons for recommending that other employment decisions be set aside or varied:

- The employee has been denied a fair hearing in circumstances where decisions have been made on the basis of adverse information or conclusions about the employee’s behaviour (with reference to warning records placed on the employee’s personnel file).

- Proper regard has not been had to the employee’s personal circumstances in applications for flexible working arrangements.

- Conditions and entitlements have been unfairly withheld from the employee (with reference to payments and leave).

Four cases were conciliated during 2017–18. In these cases, the agency or review applicant agreed to act on the Merit Protection Commissioner’s preliminary view about an employee’s case without the Merit Protection Commissioner making a formal recommendation. By the end of 2017–18 agencies had accepted all review recommendations made by our Office. Three responses were outstanding at 30 June 2018.

Box M2 discusses cases involving directions and warnings issued by agencies to employees.

Box M2: Cases about the issuing of directions and warnings to employees

We reviewed six cases in which employees disputed directions or warnings issued to them by managers in their agency. In half these cases we recommended that the direction or warning be withdrawn.

- A warning was issued by HR to a manager who had made a formal complaint under the Public Interest Disclosure scheme about the behaviour of employees in his team. An assessment was made that the manager had not used the management options available to him to address the behaviour of his team. The warning reminded the employee of his obligations, including with respect to the Code of Conduct. In our opinion the warning was potentially damaging to the employee’s reputation, the employee was not given a fair hearing and the preliminary inquiry into his disclosure raised no concerns about his behaviour.

- A manager issued a direction to an employee in response to incidents in which the employee elected to work from home without the prior approval of his manager. We concluded the direction was poorly drafted and implied that the employee had been found to have breached the Code of Conduct. It admonished the employee for previous behaviour but failed to set out the manager’s expectations for future behaviour.

- A manager issued to an employee a warning setting out the agency’s expectations in relation to the way the employee serviced clients. The status of the document was unclear, including whether it was a direction or a set of expectations, and it was variously referred to as both. We considered that the letter was disproportionate to the end it was seeking to achieve—namely, to advise the employee what was expected of her—and was not reasonable.

In three other cases we upheld agency decisions to issue directions or warnings. These concerned a direction to return to work following an independent medical examination in a case where there were differences in medical opinions; a warning to an employee to improve her performance and behaviour in specified ways; and a direction from an agency head to an employee to cease agitating on a workplace issue.

The Merit Protection Commissioner noted that directions need to be tightly drafted and in the language of command, specifying what actions should and should not be taken. Where directions seek to remove flexibility available under an agency policy, they need to be unequivocal that their intention is to create a new legal obligation.

For example, a direction about attendance should:

- set out the relevant provisions in the enterprise agreement and agency policies

- set out the employee’s obligations under the agreement and policies

- direct the employee to comply with those obligations plus any specific requirements—for example, in relation to communication with managers

- specify that the written direction is a direction for the purpose of the Public Service Act 1999

- draw the employee’s attention to the possible consequences of non-compliance with the direction.

Subject matter

In 2017–18 Code of Conduct cases accounted for 39% of all cases reviewed. Code of Conduct cases had been growing as a proportion of the total caseload in the preceding three financial years, but the trend was reversed in 2017–18.

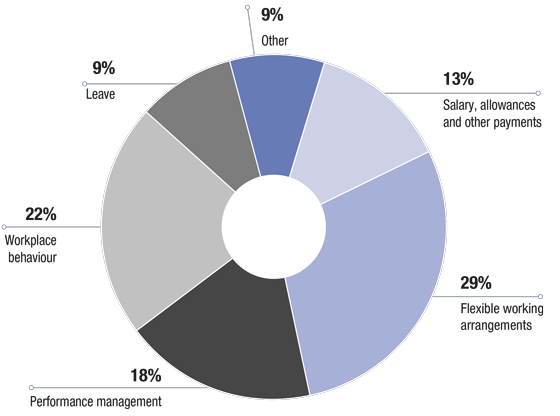

Figure M2 (below) and Table M4 in the appendix provide a breakdown of cases reviewed by subject matter, excluding Code of Conduct reviews. The majority of reviews relate to three areas of concern—access to flexible working arrangements, workplace behaviour, and performance management.

FIGURE M2: CASES REVIEWED BY SUBJECT (EXCLUDING CODE OF CONDUCT CASES), 2017–18

Breaches of the Code of Conduct

APS employees who are found to have breached the Code of Conduct can apply to the Merit Protection Commissioner for a review of the breach finding and the sanction imposed for a breach.

Based on data in the APS Commissioner’s annual State of the Service Report over the last three years, it is estimated that the Merit Protection Commissioner reviews between 4% and 10% of agency Code of Conduct decisions.*** Review by the Office offers an important avenue of review for affected APS employees and keeps under scrutiny an important area of employment decision making.

There were 55 applications for review of a decision that an employee had breached the Code of Conduct and/or the sanction and seven cases on hand at the start of 2017–18. Twenty-nine cases were reviewed during the year, involving 23 employees.**** Two applications from former employees were also reviewed.

Of the 25 cases reviewed (23 current employees and two former employees):

- Decisions in 11 cases were upheld in their entirety.

- In two cases the breach and sanction decisions were upheld but it was found that some of the factual findings could not be sustained.

- We recommended that the findings be varied in six cases—in two cases the findings of breach and in four cases the sanction.

- In six cases we recommended that the finding of misconduct be set aside in its entirety.

We recommended that the findings of misconduct be set aside in six cases for the following reasons:

- In one case the former employee was not employed in the agency at the time of the misconduct and for this reason the agency’s procedures did not apply to the employee.

- In two cases the way the investigation was conducted constituted poor practice, denying the employee a fair opportunity to respond to the allegations and resulting in a process that was both procedurally and substantively unfair.

- In one case the employee had done what the agency accused them of but they had not engaged in misconduct.

- In one case the employee was found to have engaged in misconduct on the basis of the wrong facts.

- In the remaining case we wrote to the agency about a procedural defect. The agency vacated their decision, so it became unnecessary for the Merit Protection Commissioner to make a recommendation.

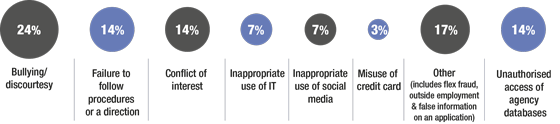

Figure M3 (below) and Table M5 in the appendix provide a breakdown of the types of employment matters dealt with in Code of Conduct reviews.

FIGURE M3: CODE OF CONDUCT CASES REVIEWED, BY SUBJECT, 2017–18

The largest area of behaviour reviewed as misconduct concerned bullying and discourteous behaviours. In all cases the behaviour was directed at colleagues or managers. The conflict of interest matters concerned personal relationships with colleagues, advocacy for family members who were also clients of the agency, a conflict between an employee’s political views and their duties, and a conflict of interest in recruitment. The social media matters concerned private behaviour—in one case misconceived but well-intentioned but in both cases adversely affecting the reputation of the employee’s agency.

There were three cases in which employees argued that their mental health should have been taken into consideration before a finding of misconduct was made. In two of those cases it was concluded that the employee had nevertheless engaged in misconduct. In the third case we recommended a reduced sanction for a range of reasons, among them the impact of the employee’s health on their behaviour.

Box M3: What review applicants say about why they seek review of Code of Conduct decisions

Review applicants sought review of determinations that they had breached the Code of Conduct and sanctions for a variety of reasons:

- They denied they had done what was alleged.

- They accepted they had done what was alleged but argued it was appropriate and reasonable behaviour and not misconduct.

- They accepted they had done what was alleged, acknowledged it was inappropriate, but argued it should not have been dealt with as misconduct, including because their behaviour was as a result of mental health issues.

- They considered there were procedural problems in the decision-making process.

- They were concerned the sanction imposed on them was too harsh.

- They were concerned about the impact of a misconduct record on their future employment prospects.

Review applicants were astute in identifying procedural problems. In six cases the review applicant’s main reason for seeking review was a procedural concern. In three cases the procedural concerns identified by the review applicant were sufficient for us to recommend that the decision be set aside. In the remaining three cases the review applicant’s procedural concerns had substance but were not of sufficient seriousness to cause us to recommend that the decision be set aside.

The language and tone of agency decisions and the way the decision-making process is conducted may be a factor in driving employees to seek review. It influences an employee’s sense of the fairness of the decision. In 40% of review applications review applicants identified this as a concern. Examples of the comments made by review applicants are:

‘The process is bullying at a departmental level and this caused me considerable personal and professional distress’. The review applicant referred to the investigation report and the agency decision as ‘repetitive’, ‘threatening’ and ‘punitive’. She stated she was forced to read and respond to several versions of ‘a very lengthy document, with multiple legislative attachments’ for what was a one-off incident. The employee advised that whatever she said in her defence ‘was used against me’.

An employee was concerned that a sanction decision maker concluded she had failed to show remorse as a result of arguments she made in her defence. The employee advised that she had ‘not attempted to direct blame to others’ but was disagreeing with the conclusions the decision maker drew from the evidence.

An employee stated, ‘I feel as though I haven’t been taken seriously, or my legitimate concerns listened to at all in this process … I am also struggling to understand how intentional misconduct was determined’.

An employee stated, ‘I take a lot of pride in my work and have done so for 40 years. To be seen by this department as being “untrustworthy” and hav[ing] a “lack of integrity” has caused me large amounts of distress … I am very embarrassed and have not shared this problem with any of my family, co-workers and only one close friend’.

An employee was concerned that when she disputed the conclusions the decision maker had drawn from the facts the decision maker concluded the employee had provided ‘false and misleading information … for expressing an opinion’.

In our view, agencies should critically assess the way they manage their misconduct investigation processes and the way they communicate their decisions. Agency decision makers need to treat the people who are subject to misconduct processes fairly and with appropriate respect and courtesy. In particular, agencies should avoid reasons for decisions that are unnecessarily lengthy and repetitive and that use exaggerated, emotive language when expressing opinions about the employee’s behaviour.

Promotion review performance

APS employees can seek a review of an agency’s decision to promote an employee to jobs at the APS 1 to 6 classifications by demonstrating that their claims to the job have more merit than those of the employees who were promoted.

In the past seven years the promotion review function has exceeded its internal performance target for timeliness (75% of reviews in time). All promotion reviews were completed within target timeframes during 2017–18.

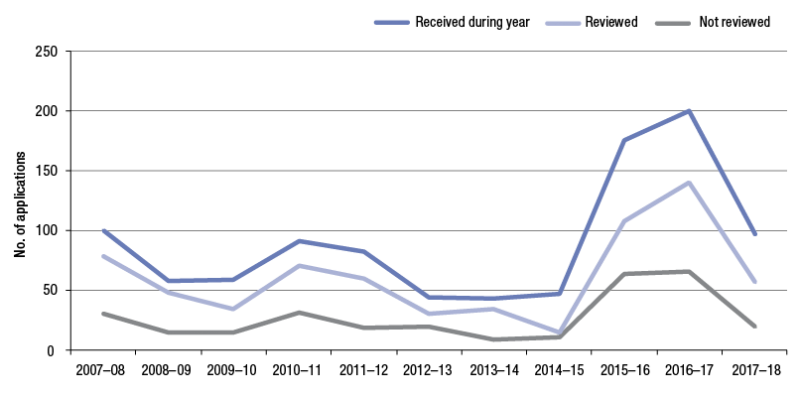

Figure M4 shows how the promotion review casework has fluctuated between 2007–08 and 2017–18. Table M6 in the appendix sets out the promotion review caseload for 2017–18.

FIGURE M4: TRENDS IN PROMOTION REVIEW CASELOAD, 2007–08 TO 2017–18

In 2017–18 both the number of applications and the size of promotion review exercises decreased to stable levels from the peaks of the previous two financial years. The previous peaks were the result of a significant increase in recruitment activity in large agencies following a freeze on recruitment as part of the Australian government’s then commitment to reduce the size of the APS.

This year the promotion review application rate decreased by 45%—97 applications were received compared with 177 in 2016–17. The Office received applications for review of promotion decisions in eight agencies. Agencies with two or more applications for review are identified in Table M7 in the appendix. Recruitment exercises in the Australian Taxation Office, the Department of Home Affairs and the Department of Defence accounted for 82% of finalised promotion reviews.

The largest number of applications for a single finalised promotion review exercise was 38 compared with 57 in 2016–17. Only six exercises had 10 or more applications, compared with 28 in 2016–17. This decrease was reflected in a fall in the average number of applications per exercise—4.4 for 2017–18 compared with 6.9 in 2016–17.

We worked with agencies to help them manage promotion review processes and to provide feedback on the effectiveness of their selection processes. The focus was agencies, such as the Department of Home Affairs, conducting bulk promotion exercises. We also discussed promotion review–related matters with the policy teams in the Australian Public Service Commission to ensure consistency of advice to agencies.

Promotion review committees provided feedback about the poor quality of review applicants’ statements made in support of their applications for review. In response, we updated information on the MPC website, providing more guidance on preparing a statement. To improve handling and security, we moved to electronic delivery of papers to promotion review committee members via the secure Govdex service.

Other review-related functions

Under Part 7 of the Public Service Regulations the Merit Protection Commissioner may:

- investigate a complaint by a former APS employee that relates to the employee’s final entitlements on separation from the APS

- review a determination that a former employee has breached the Code of Conduct

- review the actions of statutory officeholders who are not agency heads.

Table M1 in the appendix provides information on the number of applications made under Part 7 in 2017–18. Six complaints about final entitlements were received. Four applications were not accepted. One was withdrawn. In the other case we resolved the former employee’s concerns through discussion with the agency.

Two review applications received from former employees for determinations of misconduct made after they had ceased APS employment were finalised in 2017–18. These cases are referred to in the discussion of Code of Conduct decision making. A third case remains under consideration.

There were no cases seeking review of the actions of a non–agency head statutory office holder.

There was one request for an inquiry under Regulation 7.1A into the outcome of an agency’s investigation of a public interest disclosure. This remains under consideration.

The inquiry function

Under section 50(1)(b) of the Public Service Act the Merit Protection Commissioner may investigate complaints that the Australian Public Service Commissioner has breached the Code of Conduct. The Merit Protection Commissioner must report on the results of the inquiry to the presiding officers of the Parliament, including, where relevant, making recommendations for sanctions.

The Acting Merit Protection Commissioner received one such complaint in January 2018 and another in June 2018. In both cases a consultant was engaged to recommend whether the complaint should proceed to an inquiry, and in both cases the Acting Merit Protection Commissioner determined that the complaints should proceed to inquiry. A consultant was engaged to conduct both inquiries. Both matters were concluded on 7 August 2018, when the Merit Protection Commissioner provided the final report to the presiding officers of the Parliament with no recommendation for sanction.

* The survey period covered reviews finalised between February 2017 and early May 2018.

** There are benefits in reviewing findings that an employee has breached the Code of Conduct and the sanction decision at the same time. It enables the review delegate to examine the case as a whole and results in administrative efficiencies. If, however, there is a significant delay in the agency sanction decision, the breach application will be progressed separately to ensure a timely review for the applicant.

*** The State of the Service Report 2016–17 reported 530 employees were found to have breached the Code of Conduct in 2016–17. In 2016–17 we reviewed applications from 43 employees relating to breaches of the Code of Conduct and a further six were on hand. While the two sets of data do not include the same employees, a comparison over time provides an estimate that between 4 to 10% of agency decisions are reviewed.

**** Employees may apply separately for a review of a breach determination and the consequential sanction decision. Where this happens, it is counted as two cases. It is for this reason that there are more cases than there are employees.